V. Rupert García: Art for the Chicano Movement

- Taya Wyatt

I am trying to experience the truth of being alive and experiencing my moment and the moment of human beings and the situation of the world.

—Rupert García1

Rupert García is a widely-known political artist whose work appears on many posters supporting the Chicano and West Coast civil rights movements from the 60s and 70s to the present. Through his art, García focuses on the mistreatment of Latinos in the United States by emphasizing the legacy of colonial violence. The exhibition Shifting Perspectives builds on the theme of critiquing traditional visual representations of race, culture, and gender, by also bringing attention to socio-political issues. García has been an artist who supports activism since the start of his career.

Born in 1941 in French Camp, California, García’s family was the inspiration for his inclusion of folk art and Mexican artistic traditions within his work. He graduated from San Francisco School for the Arts in 1968 with a B.A. in painting. He has since received a M.A. in printmaking/silkscreen, M.A. of Art History, and Ph.D. in Art Education from University of California, Berkeley, as well as an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from the San Francisco Art Institute. Throughout his career he has built a large community of support in the Bay Area for his political actions and art work. His art has been included in almost every major exhibition of Chicano art in the United States since the 60s.

It is unknown just how many different posters and other works García has made in his lifetime. Shockingly though, every piece he has made proves his mastered skill in balancing graphic and fine art. He does this by unifying the Mexican muralist traditions of early 20th century painters Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Jose Clemente Orozco with European elements and American pop culture.

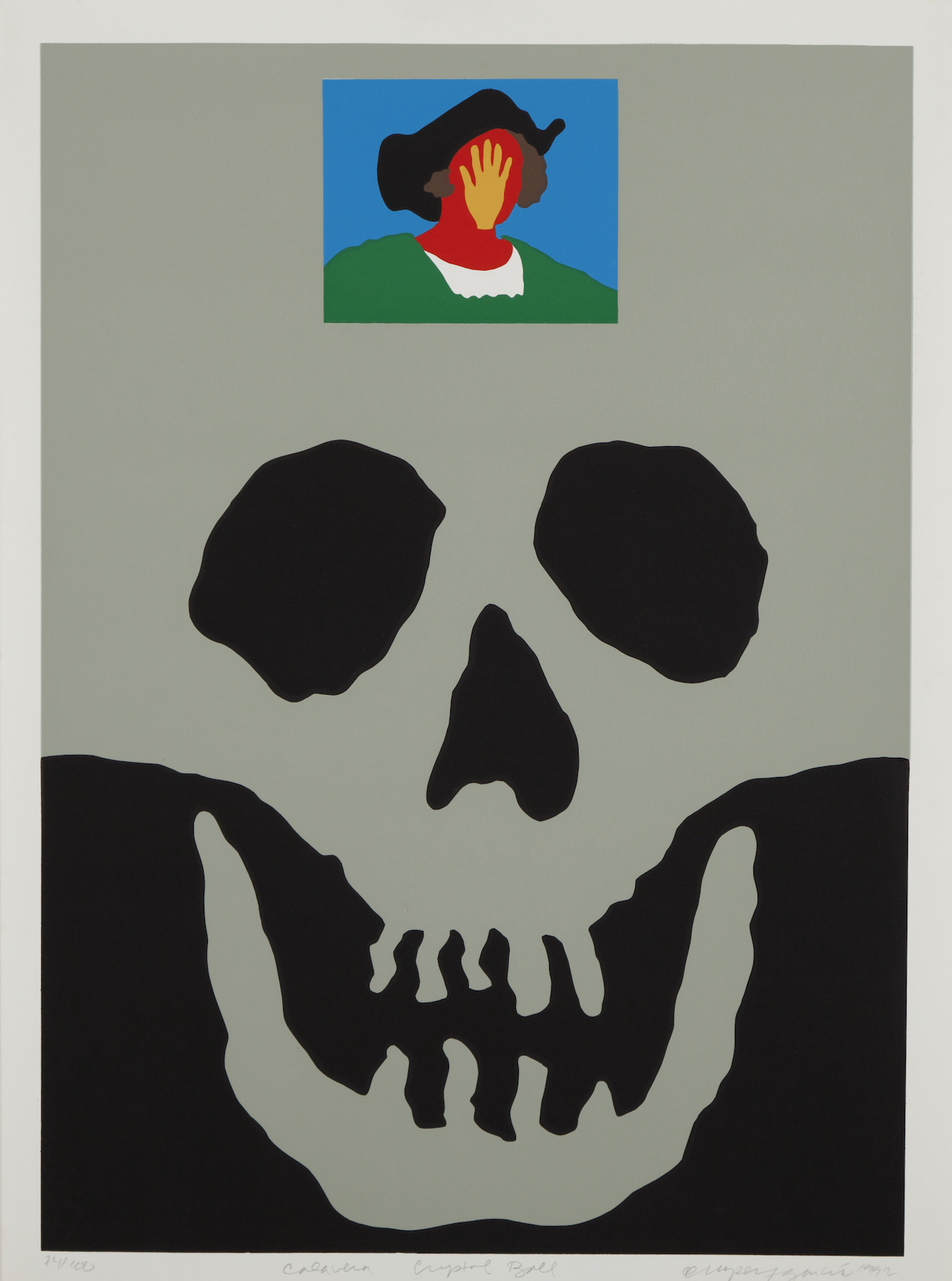

Calavera Crystal Ball is a piece that stands out from some of García’s more well-known prints (fig. 17). The medium of this print is a serigraph on paper, also known as silk screening; a process in which García is an expert. This practice is the oldest form of printmaking but wasn’t officially considered a form of “art” in the U.S. until the 1930s when artists created the term “serigraphy” to differentiate from commercial silkscreen prints.2 This print is unique because of the lack of vibrant color throughout the entirety; in most of García’s prints you find solid blocks of bold colors all over. Calavera Crystal Ball is very muted and uses mostly silver and black in the shape of a skull that stretches from each edge of the paper. On top of the skull’s head there is a featureless figure depicting Christopher Columbus with only four colors. The color choices are a signature of García’s; using complementary colors to make the figure pop out. In fellow Mills student Isabella Perry’s essay on this print, she suggests that placing Columbus above the skull gives the impression that he is no longer a hero.3 My analysis concludes that skulls were often representations of Latinx communities (as seen in the work of José Guadalupe Posada) and this image was to show that Columbus does not hold power over land that was already occupied (fig. 18).

Figure 18

Figure 18

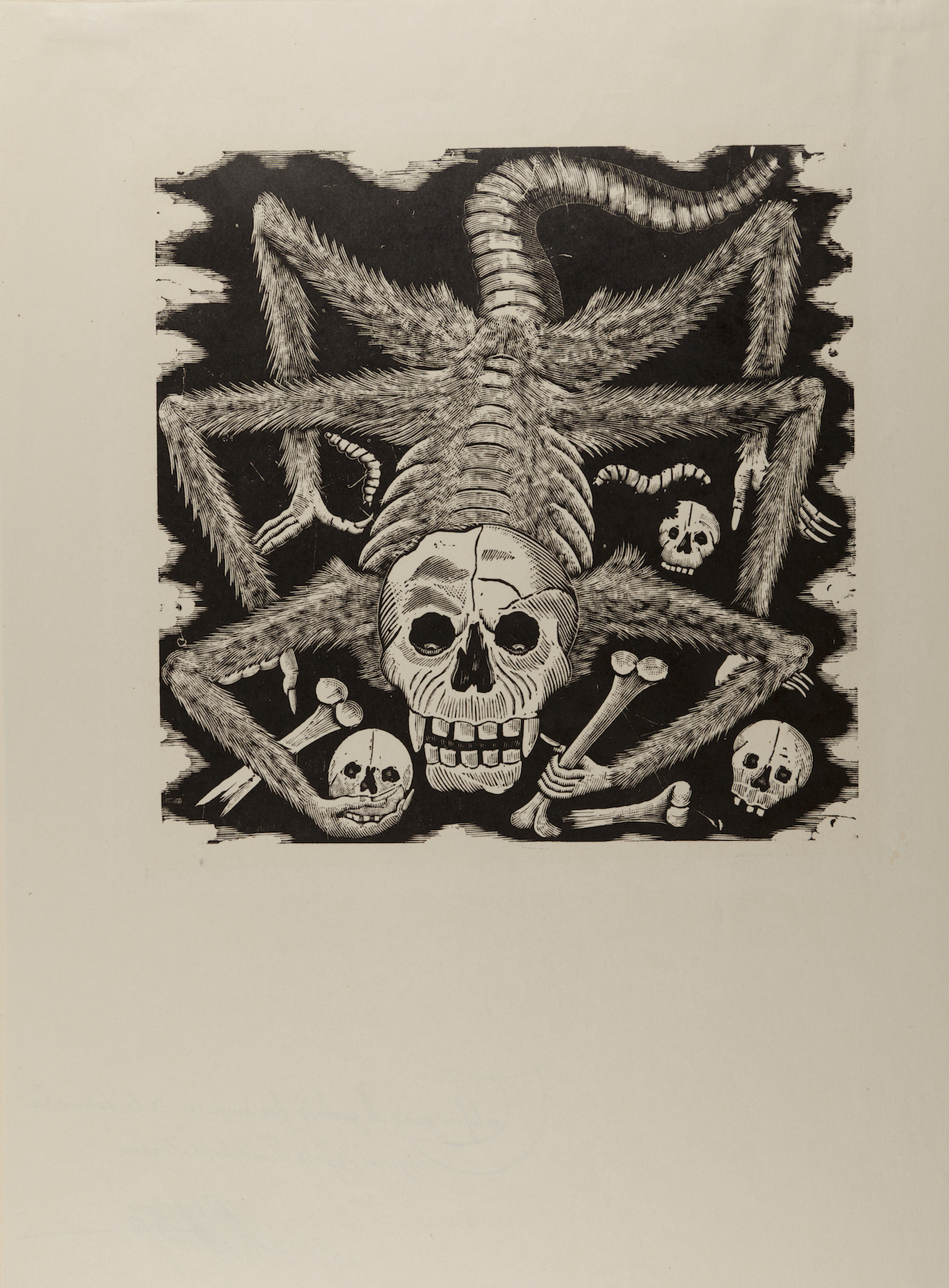

Posada was a Mexican artist known to have completed over 20,000 prints in mixed media, whose work conveyed political and cultural critiques. His images of skulls were used to embody Dia De Los Muertos (Day of the Dead). Following his death in 1913, his work gained a large following and inspired many artists, such as García. Posada tended to represent people he thought of as evil in his work in hopes of bringing more awareness to the issues of power with his art. The term calavera translates to skull in Spanish, and can be used to explore the idea that García’s skulls were also meant to evoke death upon bad people. Many of the artists who experimented with this style were inspired by the pain that colonization caused on indigenous people. The hand placed over the faceless figure gives power back to the people by not allowing us to glorify or recognize Columbus.

Figure 19

Figure 19

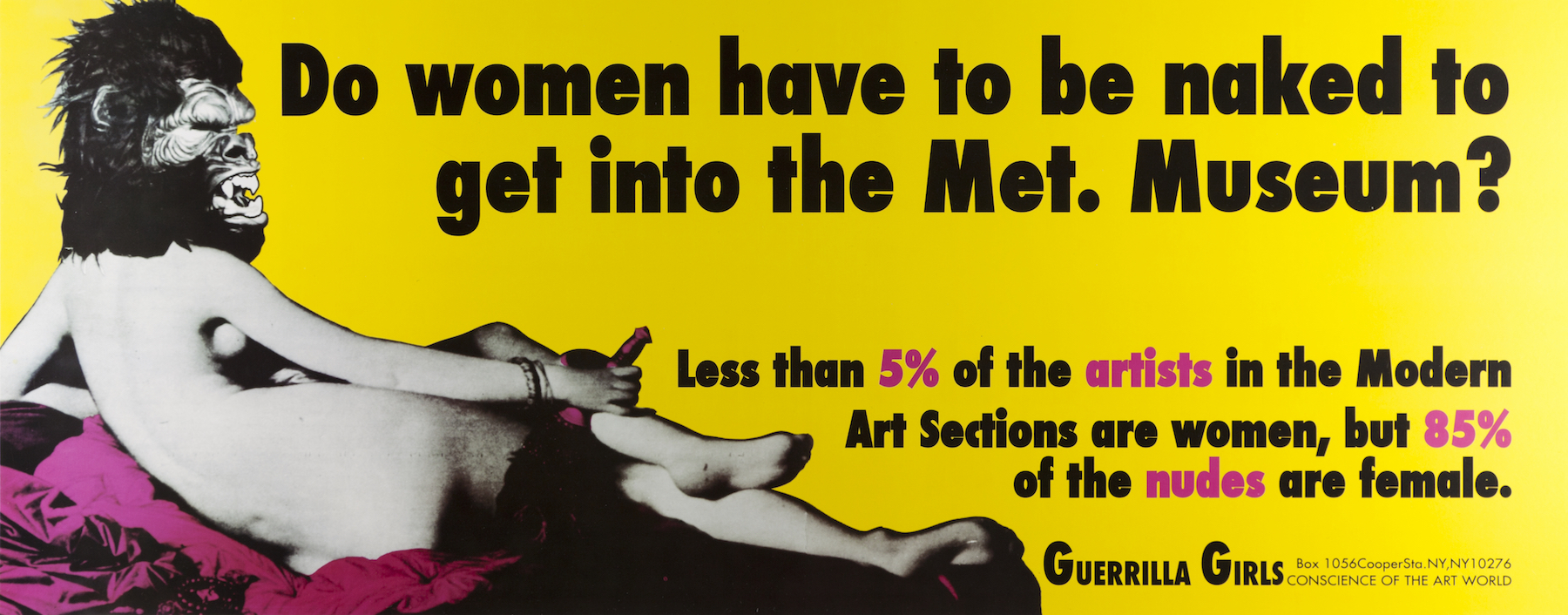

Also included in the exhibition are pieces by the Guerrilla Girls, who have said that García’s work has been an important influence. Inspired by the ease and accessibility of communicating through posters, both of these artists have been able to reach large audiences with their work. The Guerrilla Girls’ most infamous poster, included in our show, is titled “Do Women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” and started their recognition among the art community. The Guerrilla Girls are a well-known group of anonymous women who got together in the early 1980’s after the Museum of Modern Art in New York only included 13 women out of 169 artists in their International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture exhibition. Posters were commonplace, often used to advertise rock bands, films, and magazines. The Guerrilla Girls used this idea, putting their posters up all around New York City and gaining a large cult following soon after. “They made activism seem not only acceptable, but vital to full participation in the art world.”4 In this way, their work is similar to García, whose entire career has been focused on exposing political issues.

Figure 20

Figure 20

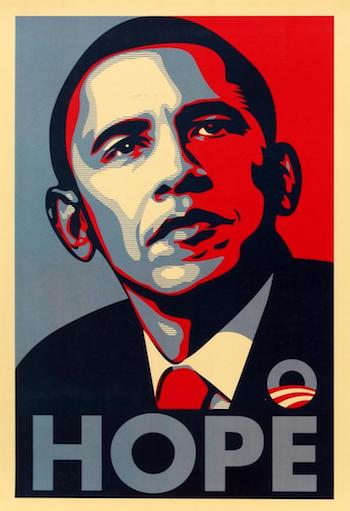

García was ahead of his time in his experimentation with posters as a vehicle for political art. M.T. Wroblewski, a reporter for Chron, wrote about the advantages of posters. He mentions how posters are capable of offering continuous exposure, are more affordable, make quick impressions, and are able to be interactive if the marketing team chooses.5 A great example of the power posters is Shepard Fairey’s Barack Obama HOPE poster that became the face of his presidential campaign. This poster would be recognized from anywhere. Linking this idea to more current times, the Black Lives Matter protests used signs and posters to emphasize their messages. Many of these signs could be seen plastered all over social media for millions of people to see.

Calavera Crystal Ball is a great addition to our exhibition as not only is the piece itself a form of activism, but the artist who made it also contributes to a progressive future. Rupert García is Mexican-American, and as a minority in the United States he has used his platform as an artist to spread positivity and power to the Latinx community. From protests to posters, García has been coined as one of the most important artists in the last 25 years.6

- Paul Karlstrom, “Oral History Interview with Rupert García, 1995 Sept. 7-1996 June 24,” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 24 June 1997, [www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-rupert-García-13572]. ↩

- “What is Serigraph Printing?” Cedar Hills Long House, September 19, 2018, [cedarhilllonghouse.ca/blogs/what-is-serigraph-printing/] Accessed November 11, 2020. ↩

- Isabella Perry, “Colonialism and Rupert García’s Prophecy of Death,” State of Convergence, (Mills College Art Museum, Oakland, 2020) , [mcam.mills.edu/publications/stateofconvergence/catalogue/rupert.html.] ↩

- Rebecca Seiferle, “The Guerrilla Girls Artist Overview and Analysis,” The Art Story, 02 Mar 2017, https://www.theartstory.org/artist/guerrilla-girls/life-and-legacy/ Accessed November 10, 2020. ↩

- M.T. Wroblewski, “The Advantages of Posters,” Small Business - Chron.com, 5 Nov. 2018, [smallbusiness.chron.com/advantages-posters-63269.html.] Accessed November 10, 2020. ↩

- “Rupert García,” Smithsonian American Art Museum, [americanart.si.edu/artist/rupert-García-1732.], Accessed November 9, 2020. ↩