IV. Mona Hatoum's Measures of Distance

- Melika Sebihi

In April of 1998, Mona Hatoum was interviewed by fellow artist Janine Antoni for Bomb Magazine. They had known each other for a few years at that point, and had even worked side by side in an exhibition in Madrid.1 Hatoum avoided getting too personal and confronting her Palestinian culture directly in her work. “It was the one occasion when I thought I’d work with the biographical,” Hatoum said on another occasion, when speaking about her piece Measures of Distance (fig. 15). “When I finished it, it was a huge relief. I thought, I can put this away and concentrate on something more subtle and abstract.”2

Figure 15

Figure 15

At one point during the Bomb interview, Antoni makes the observation to Hatoum that, “Everyone seems eager to define you”—commenting on the ways in which viewers and critics apply their understanding of Middle Eastern people to Hatoum’s work, despite Hatoum’s desire to avoid being essentialized and othered. Hatoum’s response to Antoni’s remark makes it clear that she is concerned with the problem of representation:

MH: I dislike interviews. I’m often asked the same question: What in your work comes from your own culture? As if I have a recipe and I can actually isolate the Arab ingredient, the woman ingredient, the Palestinian ingredient. People often expect tidy definitions of otherness, as if identity is something fixed and easily definable.

JA: Do you think those kinds of questions have made us overly self-conscious about how we represent ourselves and its effect on the work?

MH: Yeah, if you come from an embattled background there is often an expectation that your work should somehow articulate the struggle or represent the voice of the people. That’s a tall order really. I find myself often wanting to contradict those expectations.3

Contradiction of expectations is just what brought Hatoum’s video Measures of Distance to the exhibition Shifting Perspectives. In many ways, Hatoum’s work serves to critique traditional representations of Arab women—despite the fact that Hatoum wished to distance herself from the expectation to speak for Arab issues to which she did not consent. Because of her dedication to representing the trauma of displacement, her work productively grapples with the problem of expectations.4 Measures of Distance, a fifteen minute and twenty-six second video of the artist’s mother, deals with various themes including war and deportation. This deviates from the Orientalist norm, representing Arab women in a complex way that does not serve the Western fetishist gaze. Her artistic style, perspective, and her positionality as a Palestinian artist brings a unique viewpoint to Shifting Perspectives that adds a valuable and unique voice to the various artists represented.

Mona Hatoum is a Palestinian artist who was born in Lebanon. She was subsequently forced to stay in to England after war broke in Lebanon, displacing her from her homeland.5 Like many women refugee artists, such as Cuban-born Ana Mendieta, Hatoum’s work both obviously and covertly speaks to themes of banishment, expatriation, and exile. Measures of Distance discusses these themes through a seamless combination of the personal and political. The piece itself is video footage of Hatoum’s mother. The footage is hazy; combinations of dark blues, purples, and greens make up the image of Hatoum’s mother, naked in the shower. The video is overlaid with Arabic script, taken from letters that the artist’s mother wrote from Beirut while Hatoum was in England. This text is read aloud in English by Hatoum.6 The script not only provides context for the viewer, but also partially obstructs the image. Along with the translation of the text being read aloud by Hatoum, the audio also features taped conversations between herself and her mother. In these conversations, they speak openly about their feelings, including topics like sexuality, prompting Hatoum’s father’s “objections to Hatoum’s intimate observation of her mother’s naked body.”7 These conversations are described poetically by journalist Rachel Spence, who described the audio as “whispers of love and exile flickering through the bars of their calligraphic cage like a faulty, seductive current.”8

Many of Hatoum’s stylistic choices lend themselves to the themes of Shifting Perspectives. This student-curated exhibition is meant to focus on artists’ critiques of visual representations of identity—including gender and cultural heritage. These critiques often come in the form of subversion, or reckoning with what is expected in order to call attention to power dynamics like sexism. For example, Hatoum once spoke of the inner turmoil she experienced when wondering if she should use the footage of her mother, naked in the shower, for Measures of Distance. In the 1980s when this work was created, Hatoum observed that there was so much disagreement over the feminist implications of the female nude that many representations of women in art had faded away altogether.9 The artist describes this absence as depressing, and decided to use the footage in an unexpected way, placing Arabic script from her mother’s letters over the footage, and interweaving audio of both Hatoum reading the letters in English and intimate conversations between her and her mother. The act of placing her naked mother within a socio-political context using these conversations about displacement, exile, and horrific loss leads to a reading of her work that sees Hatoum’s mother as both non-sexual and non-passive.10 This subverts the expectation (rooted in Orientalism) of passivity and sexualization that the Western gaze has when it comes to Arab women, shifting our perspective to see both personal humanity and political context rather than a simplified stereotype.

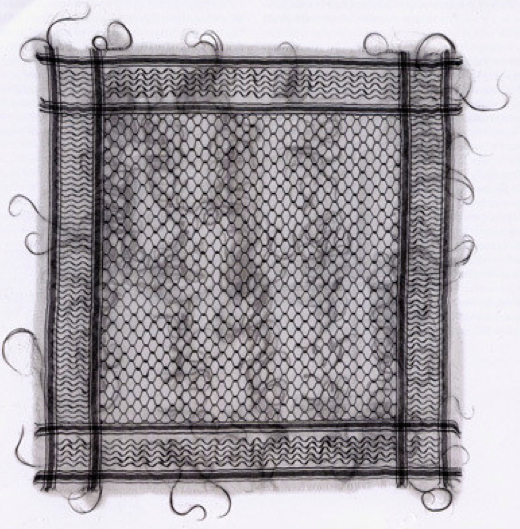

The Arabic script that filters Measures of Distance both distorts and informs the video’s message, partially hiding the footage while adding context through the content of the letters. Janine Antoni describes the script as a type of veil, adding layers of meaning to the piece.11 This description of the script as a veil is somewhat paradoxical—Hatoum speaks of her “rebellious and contrary attitude” to Arab stereotypes yet conforms to this somewhat essentialist understanding of the Arab woman.12 However, art historian Jaleh Mansoor points out that within the political context of the Israel-Palestine conflict, the veil was considered a symbol of resistance. Hatoum calls upon the veil in other works such as Keffieh (fig. 16). The keffiyeh is a headscarf traditionally worn by Palestinians, and functions as a symbol of solidarity between Palestine and Western countries. Hatoum later confirms that her intent was to create a “potent symbol of Arab resistance.”13 Similarly, in Measures of Distance, the “veil” has a deeper meaning. While the footage and audio connotes intimacy and closeness, the script creates a barrier. Moreover, the fact that the script is taken from letters implies a distance or farness between her and her mother. This allows us to perceive the figure while not having full access. In this way, Hatoum literally and figuratively obscures our perspective.

Figure 16

Figure 16

Mona Hatoum’s identity reflects her confrontation of socio-political issues in her work. Like many of the works in this exhibition, Measures of Distance reflects the lived experience of the artist. Similarly to artists Faith Ringgold and Shahzia Sikander, Hatoum defiantly reclaims the female body through the subversion of cultural stereotypes. Hatoum weaves the personal, empathetic relationship between a mother and daughter with political themes of agency: war, patriarchal values, and exile to express the complicated nature of Arab feminism. This serves to both humanize and politicize the Middle Eastern experience, creating a space for Hatoum to express her lived experience as an Arab feminist refugee without isolating the essentialist “Arab ingredient.”14 Hatoum’s Measures of Distance is not included in Shifting Perspectives for abandoning tradition, but rather, creating a visual compromise between what is expected and what is true. This compromise, along with the balancing act between the personal and the political, lends itself to the exhibition’s mission to show how artists resist expectations through changing viewpoints, or shifting perspectives.

- Janine Antoni and Mona Hatoum, “Mona Hatoum,” BOMB, no. 63 (1998): 56. ↩

- Rachel Spence, “Mona Hatoum: A Sense of Unease,” FT.Com (Jan 19, 2018). ↩

- Antoni, “Mona,” 54. ↩

- Kimberly Lamm, “Seeing Feminism in Exile: The Imaginary Maps of Mona Hatoum,” Within Hostile Borders (Ann Arbor: MPublishing,2004), 18. ↩

- Elizabeth Manchester, Mona Hatoum: Measures of Distance, Tate Britain (February 2020), [https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hatoum-measures-of-distance-t07538]. ↩

- Museum of Modern Art, “Mona Hatoum - Measures of Distance,” (2013). [https://www.moma.org/collection/works/118590]. ↩

- Manchester, “Mona.” ↩

- Spence, “Mona Hatoum: A Sense of Unease,” [https://login.intra.mills.edu:2443/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.intra.mills.edu:2443/docview/2002890493?accountid=25251]. ↩

- Antoni, “Mona”, 57. ↩

- Manchester, “Mona.” ↩

- Antoni, “Mona”, 58. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Jaleh Mansoor, “A Spectral Universality: Mona Hatoum’s Biopolitics of Abstraction,” October 133 (2010): 49-74. Accessed November 1, 2020. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/40926716]. ↩

- Antoni, “Mona”, 56. ↩