I. Faith Ringgold's French Collection: Jo Baker's Birthday

- Simone Gage

You asked me once why I wanted to become an artist. It is because it’s the only way I know of feeling free. My art is my freedom to say what I please.

— Willia Marie Simone, in The French Collection, Part I1

Jo Baker’s Birthday (1995) is not only a testament to such French icons as Josephine Baker, Édouard Manet, and Henri Matisse, but a reimagined version of art history which is centered around the experience of Black women. Faith Ringgold’s French Collection encompasses Ringgold’s own reflection on what it means to be a Black American, a woman, and mother of two who aspires to be an artist. Ringgold illustrates the complexities of her multifaceted identity in this series of quilts while both critically confronting and paying homage to the lasting impact of eighteenth and nineteenth century white male European artists. She does so through the fictitious life of her heroine Willia Marie Simone, living vicariously through Willia’s many encounters with iconic European painters. Initially these pieces can be perceived as a celebration of the contributions of such visual artists—which in addition to Manet and Matisse include Picasso and Van Gogh—and French monuments such as the Louvre. And yet pieces from the collection, such as Jo Baker’s Birthday, transparently convey Ringgold’s desire to shift the perspective away from the achievements of male European painters and quite literally bring the experience of Black women into the foreground. In conversation with the selected pieces from the Mills College Art Museum featured in the exhibition Shifting Perspectives, Jo Baker’s Birthday carries a powerful and continually relevant message conveying the often overlooked but extremely significant roles of Black women in art history.

Born in Harlem in 1930, Faith Ringgold came from a close family whose love of storytelling was an important early influence. By her senior year of high school, Ringgold had decided that she wanted to become an artist. In the seven years she spent earning a Bachelor’s degree in Art Education at New York’s City College, Ringgold had married, divorced, and had given birth to two daughters within a year of each other.2 Her artistic career began in the early 1960s after the completion of her Masters of Fine Arts degree in 1959. Inspired by the artwork she was exposed to in her college courses, Ringgold took her mother and two young daughters on a trip to France to view the masterpieces she had studied in person. Her time in Europe had greatly impacted her artistic practice; upon her return home, Ringgold felt compelled to transform what was formerly her dining room into an art studio. She strove to create images of Black people—drawing upon the experiences of everyday people by producing portraits of her family and members of her community—whose images had otherwise been absent in her formal art education.

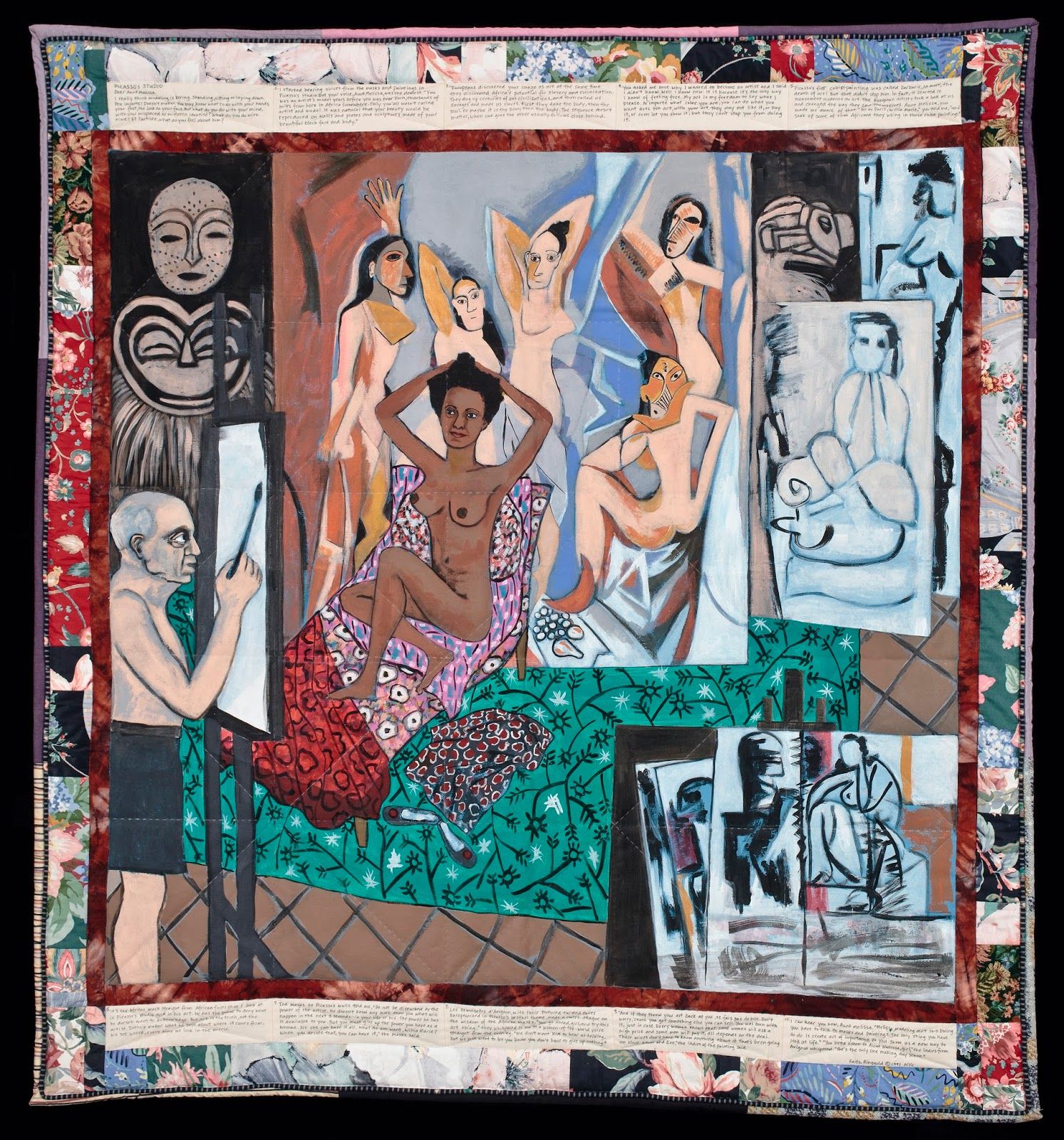

With twelve quilts in total, The French Collection is her most complex work to date: an artistic narrative in textile form in which Ringgold inserts an African-American presence into the tradition of Parisian modernism in which she was trained. Her protagonist is a young African-American woman, Willia Marie Simone, who goes to Paris to study art in the 1920s.3 Willia Marie is not only the heroine of Ringgold’s narrative quilts but also her alter-ego. The handwritten text on the borders of each quilt reveals that, like Ringgold, Willia Marie confronts her struggles of being an aspiring artist and mother of two young children, seeing her time in France as an attempt to find meaning in both her own life and in her art. Throughout her time in Paris, Willia Marie addresses issues of racism and colonization in both America and France and the complexities of her own identity in relation to the Eurocentric study of art history that has prevailed in Western education. Through Willia, Ringgold asserts that, rather than being models and muses, women can be the speaking subjects of their lives. While posing in Picasso’s Studio (1991) (fig. 1), Willia is fondly encouraged by the African masks in his masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) to pursue a career as an artist, insisting that she doesn’t have to give up anything to make her dream a reality. As a series, the quilts are a strong affirmation of the creative authority of Black women and their unacknowledged contributions to art history.4

Figure 1

Figure 1

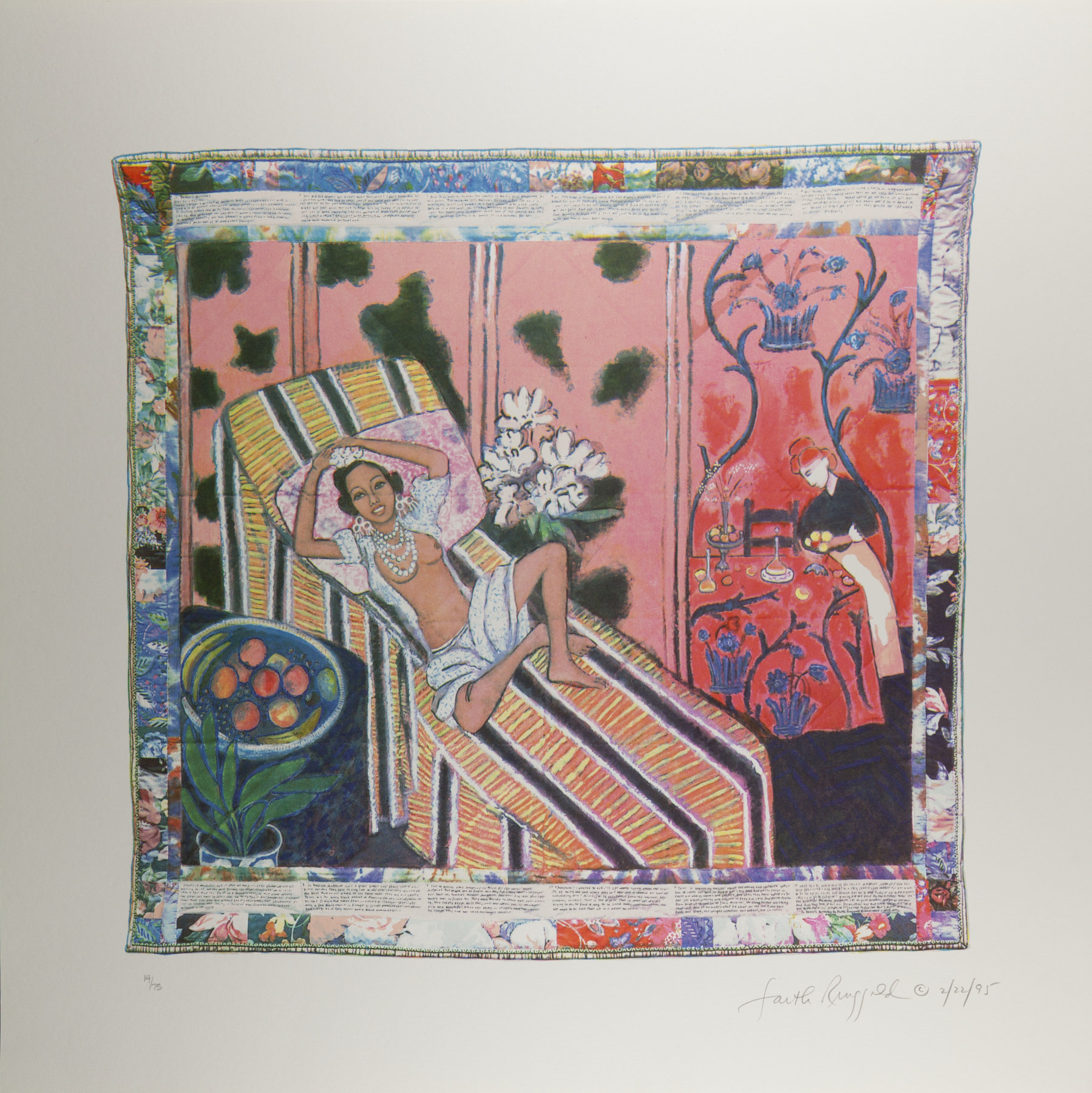

Figure 2

Figure 2

Jo Baker’s Birthday provides an alternative to the Eurocentric tradition of art while still acknowledging the undeniable influence of artists such as Matisse and Manet (fig. 2). Ringgold sets a recognizable scene with combined elements from Manet’s Olympia (1863) and Matisse’s The Dessert: Harmony in Red (1908). In the left foreground is the reclining, partially nude figure of Josephine Baker, a Black American expatriate in France working as a dancer and entertainer. Her body is ornamented with jewels, luxurious fabrics, and on the crown of her head sits a large white flower. Her serene expression and relaxed pose further add to her aura of opulence. Along the borders of this quilt is text meant to be read in the voice of Willia Marie, whose words reflect on the attitudes toward Black women in America and France. Willia explains that the “reality is that Josephine is Black, and they would never have let her seek fame and fortune in the States. There her talent would be no talent at all. Her dance would be no dance at all. Her voice would be no voice at all. Her greatness would be no greatness at all … Her life would be no life—no beauty.”5 This quote sheds light on Ringgold’s own consideration of what it means to be a Black female artist in America—a sentiment that she perhaps felt was still relevant in the time she created this piece. In the bottom left corner sits a basket of assorted tropical fruit, which Ringgold likely includes as a reference to Dutch still life painting and the demonstration of individual wealth embodied by one’s imperialist possession of exotic fruits. Additionally, the decision to include bananas in this assortment may also be intentional. The history of the banana is intrinsically linked to European imperialism and the enslavement of those forced to work on banana plantations, namely in the Caribbean. Furthermore, the phallic shape of the banana has transfigured the tropical fruit into a symbol of sexual desire or deviance; in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, proper fruit-eating etiquette was expected of esteemed European women to avoid such implications. Conversely, in the 1920s Baker became famous for performing her signature Danse Sauvage in Paris while wearing a costume consisting of only a beaded necklace and a skirt made from artificial bananas. And so her portrayal in Jo Baker’s Birthday serves as a tribute to her complex social identity and bold sexuality, as she is depicted as being unbothered—and even empowered—by her nudity.

Figure 3

Figure 3

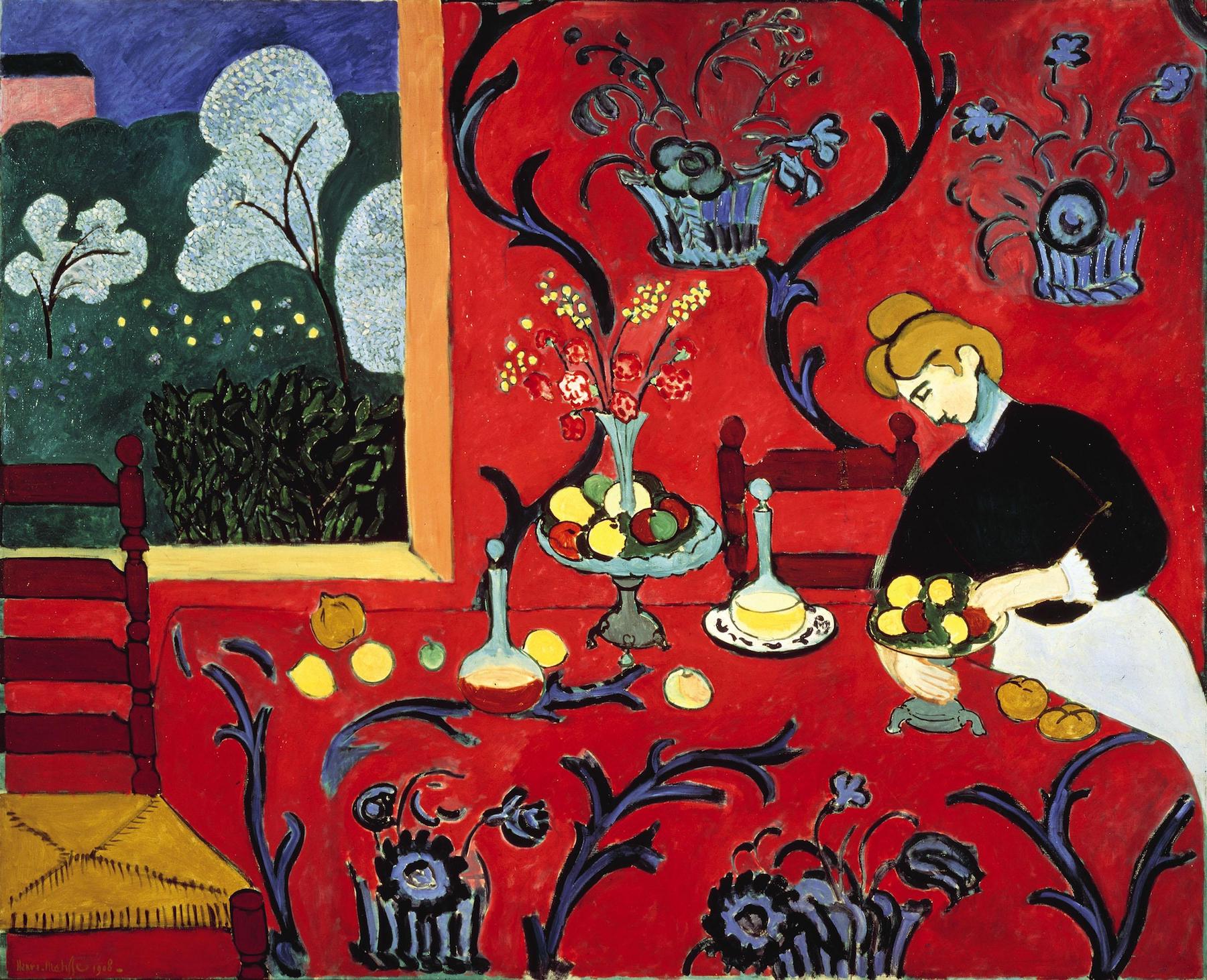

The arrangement of the two figures—Baker and her anonymous maid— in this space recall that of Manet’s Olympia, especially when considering the reversal of social roles (fig. 3). Olympia presents Olympia, a white courtesan, in the foreground. She is laying on a bed topped with what appears to be a silk sheet, her upper half propped up with two large pillows. Her nudity is emphasized by her sparsely-clad accessories, including a pair of heels, a thin black choker necklace, a gold bracelet on her wrist, and a large pink flower tucked behind her ear. Her right hand covers her genitalia, calling further attention to her nudity. Set into the middleground, her Black maid presents Olympia with a large bouquet of fresh flowers. Her eyes settle on the face of Olympia as she leans forward, lips parted as if she were about to speak, and yet Olympia’s gaze is fixed on us, the viewer. Jo Baker’s Birthday borrows these figural elements, positioning Baker as Olympia and the white female figure in the background as the equivalent to Olympia’s maid. Ringgold has quite literally replaced the prominence of Olympia with that of a Black female icon, being doted upon by her white maid who is of secondary importance. The figure of the maid and her immediate environment are derived from Matisse’s painting The Dessert: Harmony in Red in which a woman is shown leaning over a table and arranging fruit in a crystal bowl (fig. 4). She stands in a red room adorned with vases, flowers, and ornately designed tablecloth and wallpaper. Ringgold has appropriated this imagery, setting it into the background of Jo Baker’s Birthday.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Her reference to Manet’s Olympia is integral to our understanding of Matisse’s figure as being Baker’s maid; her social role in the painting is framed by the implication that she is preparing the house for Baker’s birthday celebration. This is reinforced by the large arrangement of flowers to the right of Baker that we might assume were presented to her by this background figure in the same fashion that Olympia’s maid offered her a bouquet. This social reversal forces us to readdress the maid in Olympia, a figure long dismissed in art history as merely serving the function of creating a racial juxtaposition between herself and Olympia, and whose presence is meant to reinforce that nefarious behavior is in tandem with overt female sexuality. Through her use of a Black female icon such as Baker whose nudity was a form of self-empowerment, Ringgold emancipates Olympia’s maid from these previous notions and elevates the role of Black women in art history to that of celebrated liberation.

Figure 5

Figure 5

The works featured in Shifting Perspectives asks us as viewers to consider this deviation from those which historically have been most prominently featured in the art world, and instead take some time to redirect our attention to the achievements of those who have spent their artistic career shedding light on socio political issues of inequity, disenfranchisement, or who simply strive to celebrate the accomplishments of marginalized communities. In addition to Jo Baker’s Birthday, presented in the form of a silkscreen print from the series Ten Women/Ten Prints, Carrie Mae Weems’ piece Commemorating Every Black Man Who Lives to See Twenty-One (1992) provides a similar sentiment (fig. 5). This piece is one in a series of plates which Weems commissioned the American china producer Lenox—known for their production of customized dinner plates and tableware for the White House, U.S. Embassies, and governors’ mansions—to produce commemorative plates honoring the achievements and cultural contributions in Black American history, both grandiose and tragically simple. Traditionally these porcelain plates are used to acknowledge the political accomplishments of the wealthy elite; Weems transforms this material representation of disproportionate wealth and power into a recognition of the significant contributions of Black Americans to U.S. history, including Commemorating Blues, Jazz, Collard Greens & Thelonious Monk and Commemorating Jo Ann Robinson, Claudette Colvin, Rosa Parks for Not Getting Up. Given the 2020 resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in protest of police brutality and systemic racism in the United States, Weems’ reminds us that the grim message inscribed on this plate is just as relevant now as it was when she created it in 1992. Both Ringgold and Weems compel us as viewers to acknowledge those whose contributions to history have been rendered invisible within the bastion of white patriarchal hegemony and the sociopolitical structures that have concealed them, and transmogrify symbols of this anachronistic authority into celebrations of resistance, revitalization, and diversity.

- Melody Graulich and Mara Witzling, “The Freedom to Say What She Pleases: A Conversation with Faith Ringgold,” NWSA journal 6, no. 1 (1994): 1. ↩

- Graulich and Witzling, “The Freedom to Say What She Pleases,” 1. ↩

- Graulich and Witzling, “The Freedom to Say What She Pleases,” 4. ↩

- Graulich and Witzling, “The Freedom to Say What She Pleases,” 4-5. ↩

- Faith Ringgold, Dancing at the Louvre: Faith Ringgold’s French Collection and Other Story Quilts, University of California Press (1998): 141. ↩