Thea Moerman

“For me to really understand anything, I have to take it into my body.” — Christine Cassidy, The Persistent Desire, edited by Joan Nestle, 1992.

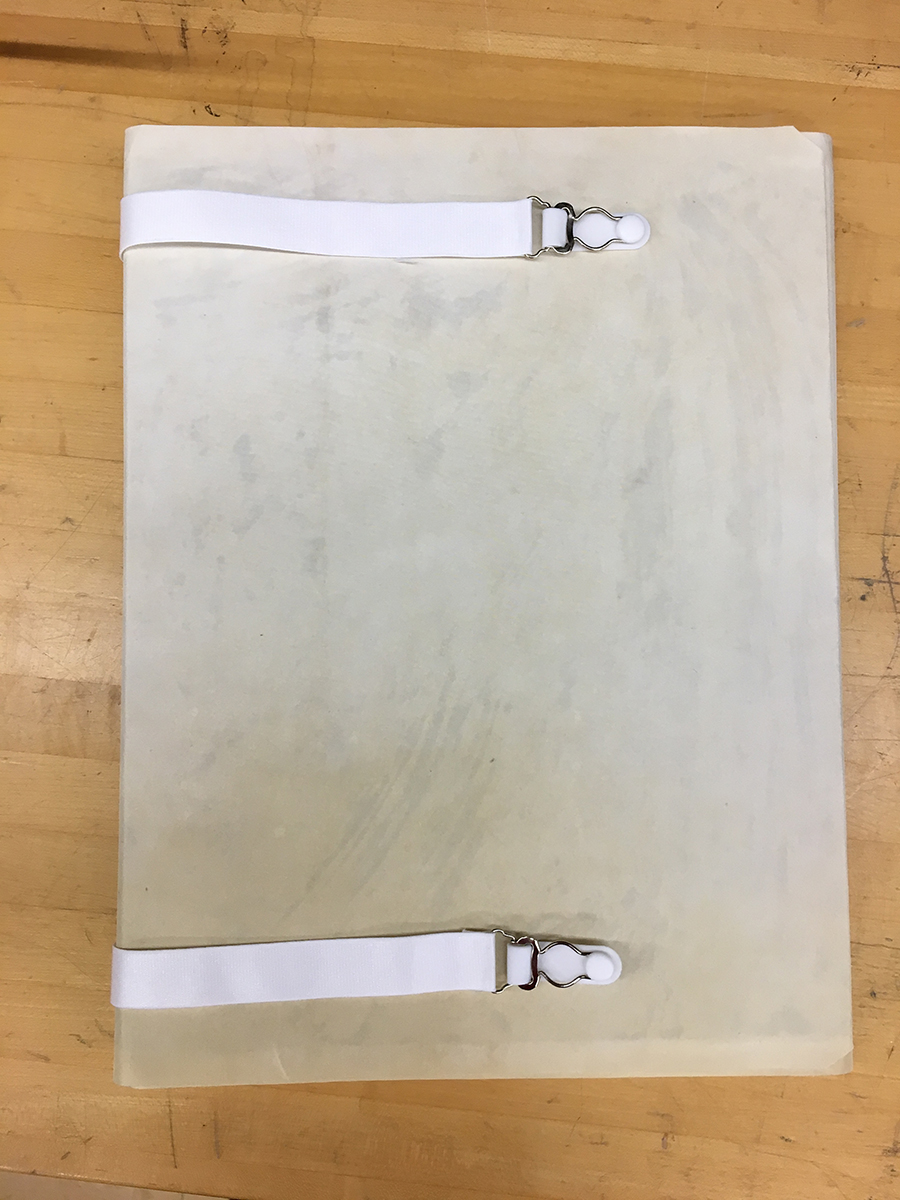

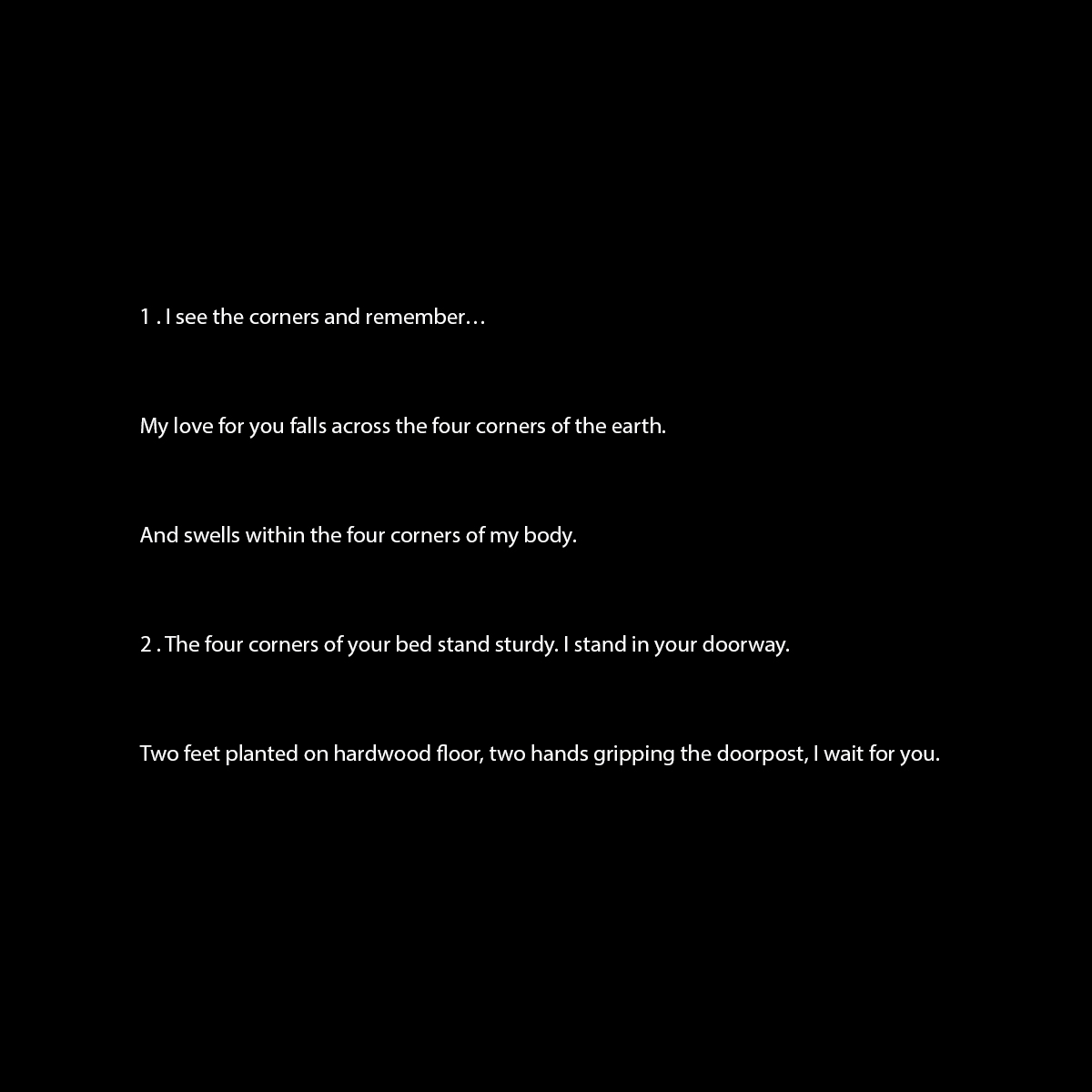

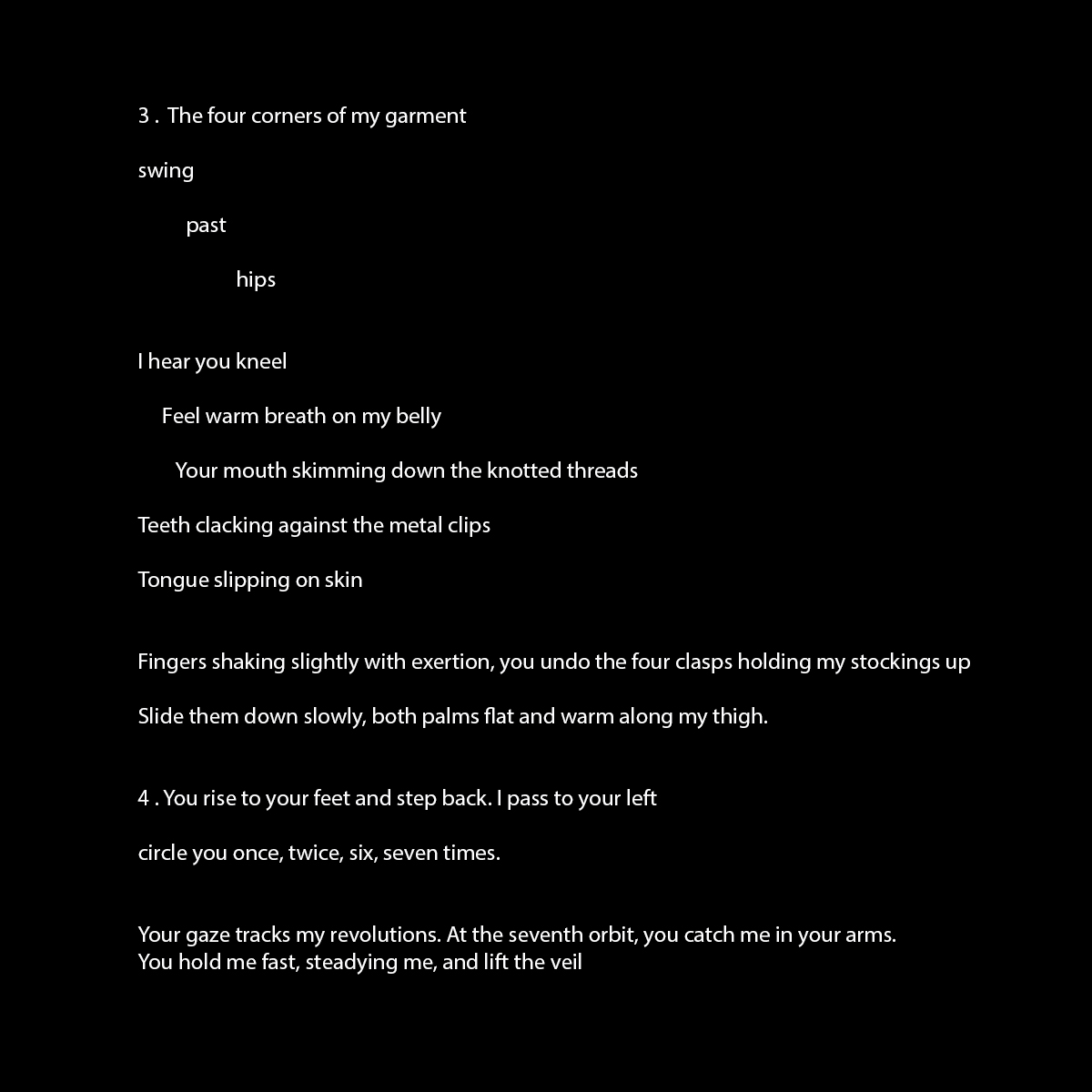

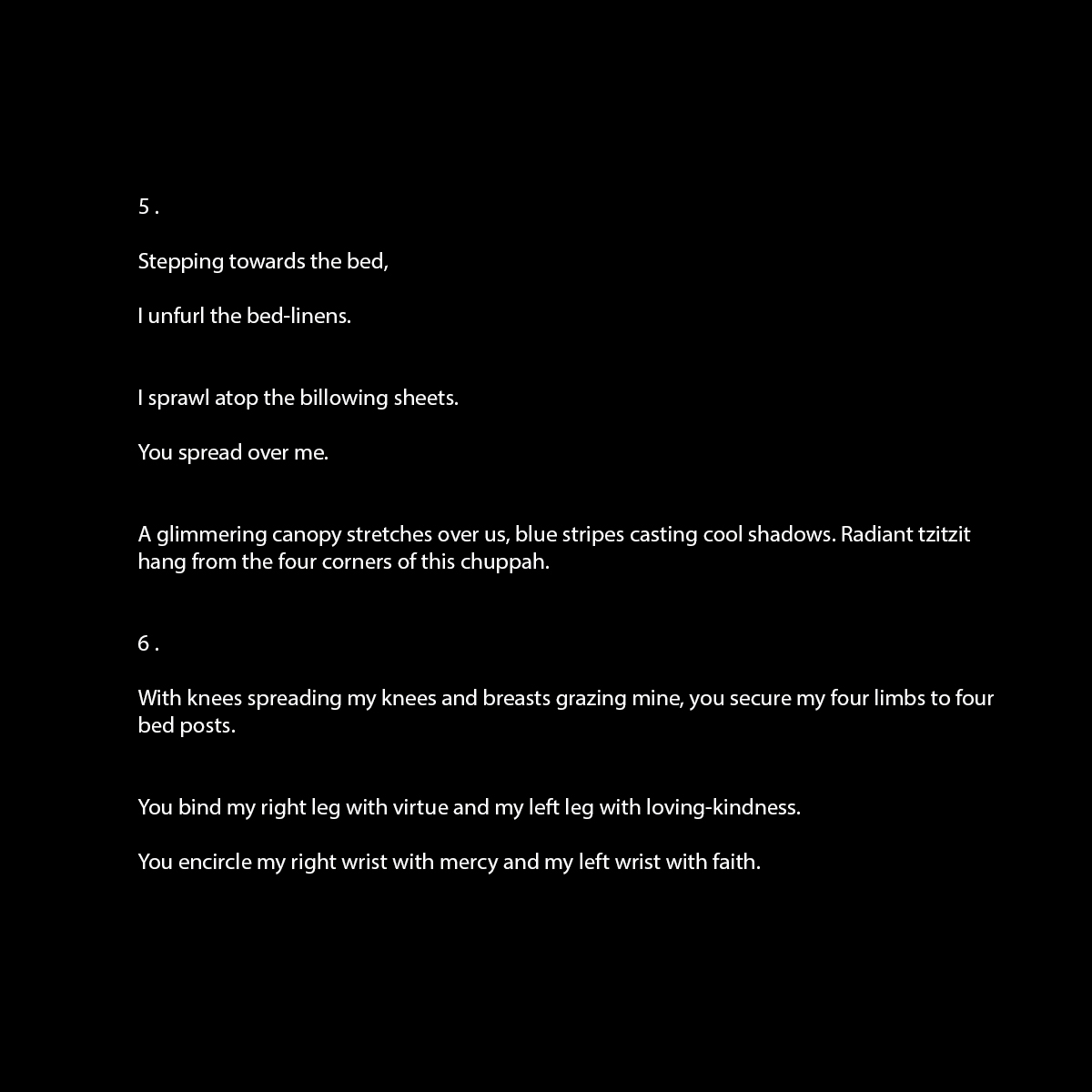

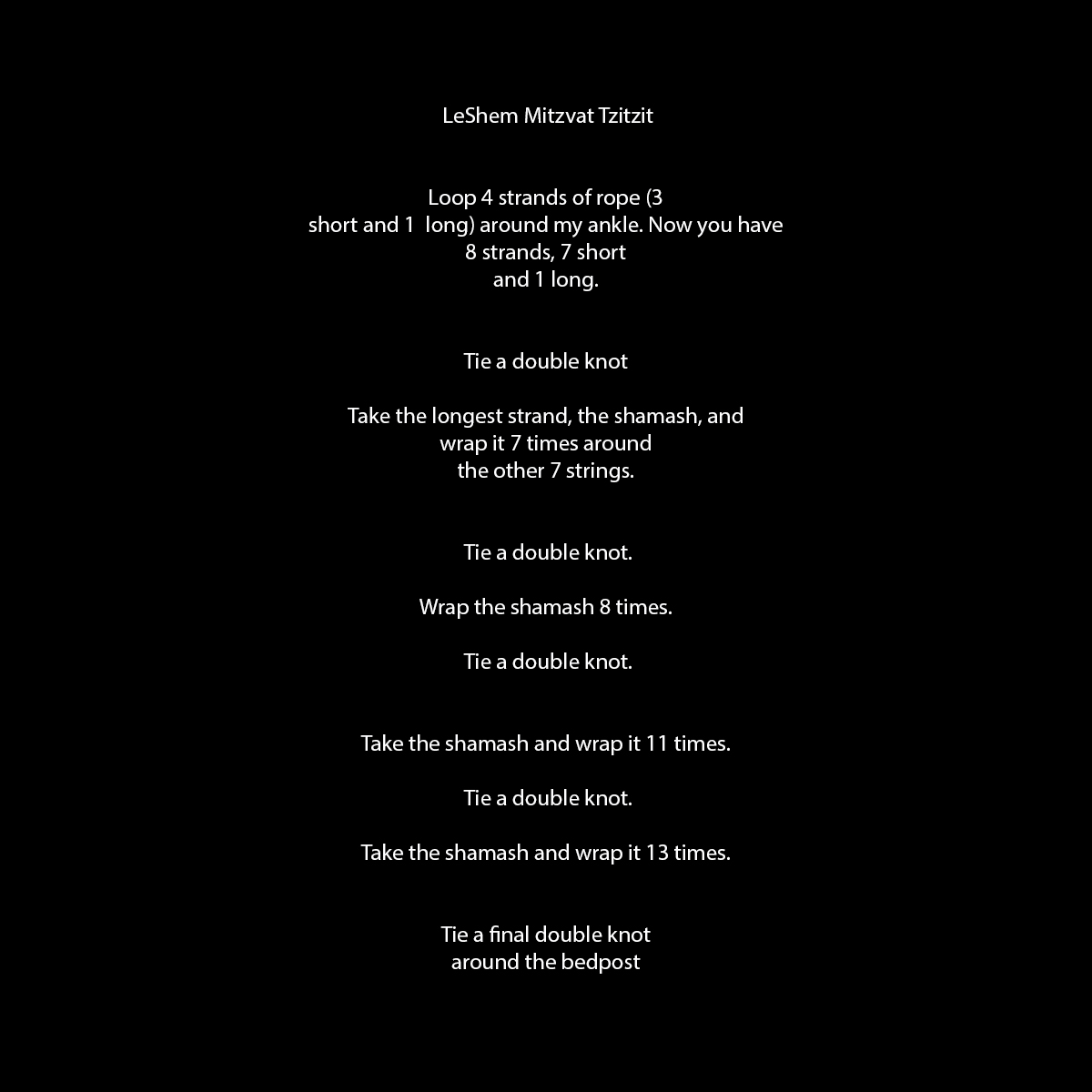

My first time strapping on a dildo overlaps in my imagination with my first time laying tefillin. Putting on lingerie piece by piece, sliding stockings up my legs, straightening the seams, snapping them in place with four or six garter clips, is a ritual on par with religious dress—putting the tallit katan on under my shirt, smoothing the loose material down, tucking my shirt into my pants, tightening my belt, pulling the tzitzit out under my belt so they are held in place and my outer shirt stays tucked, so I am reminded on all four corners. This religious dressing ritual has an erotic power as well. I feel equally the eroticism of religion (wrapping tefillin, kissing mezuzot, bending and shaking in prayer) and the divinity of fucking (the transcendentality of being filled with a fist, mouths, rope or leather binding my body and soul).

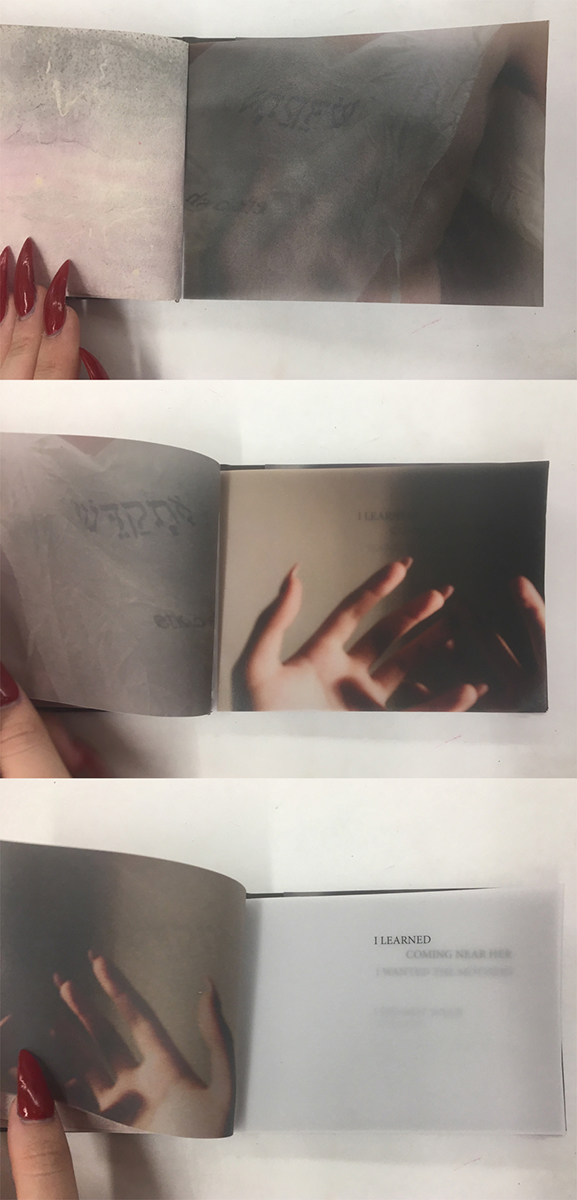

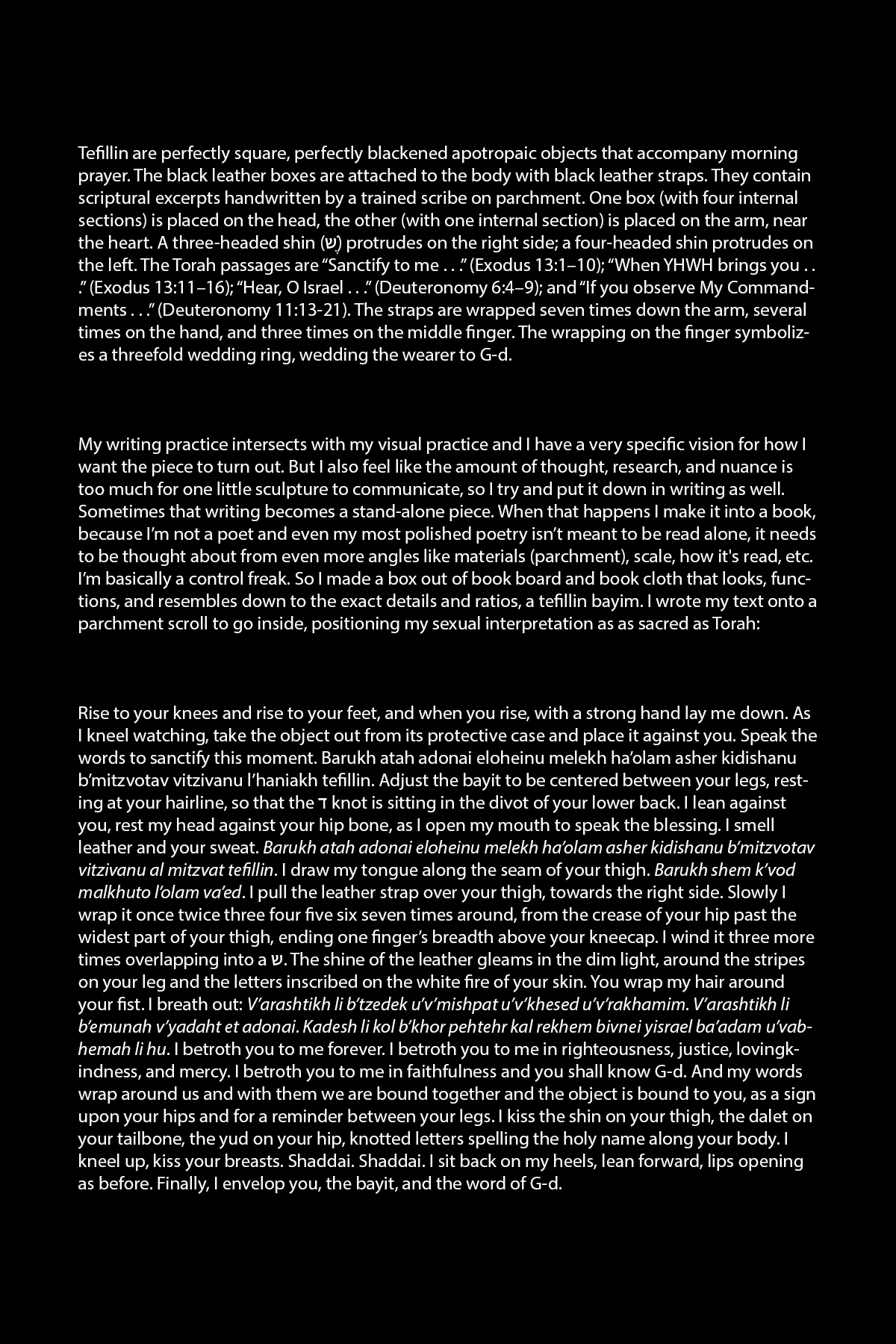

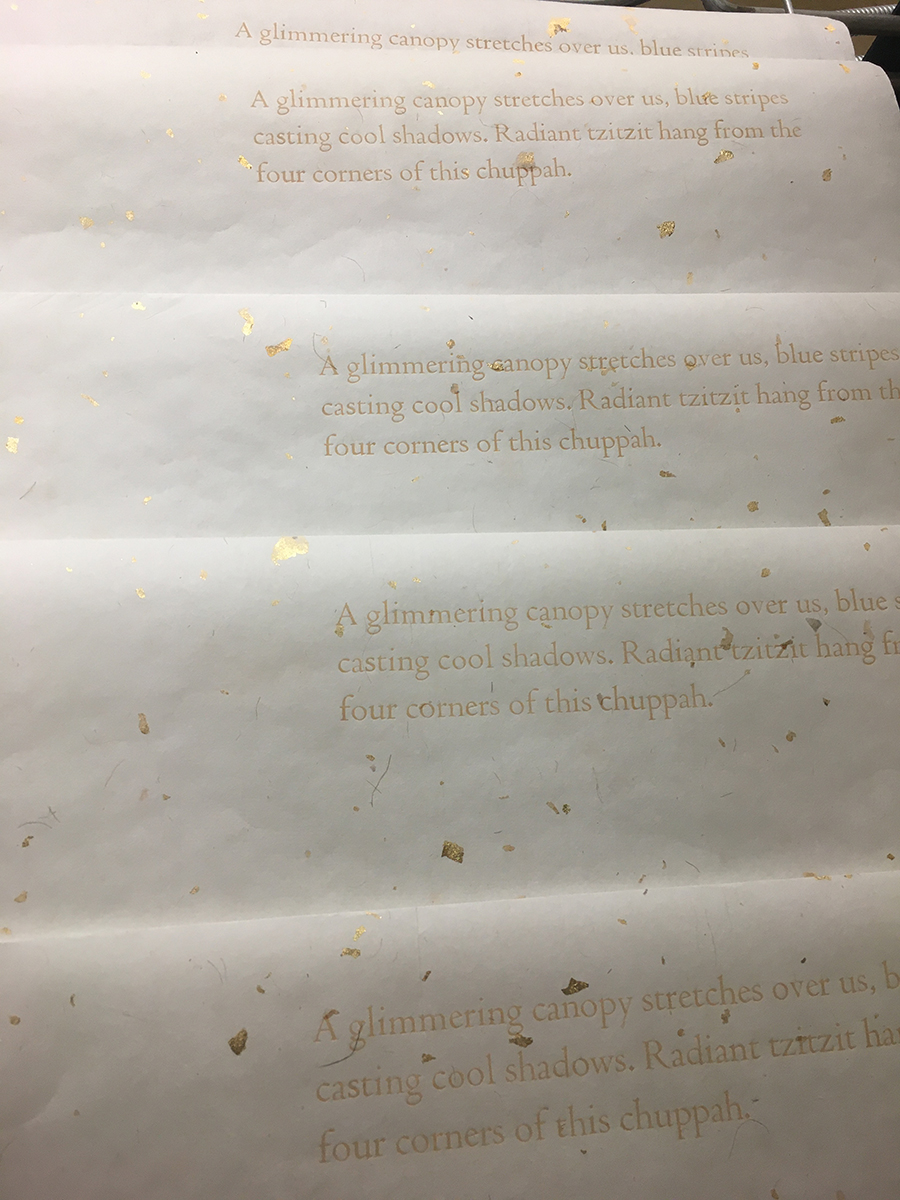

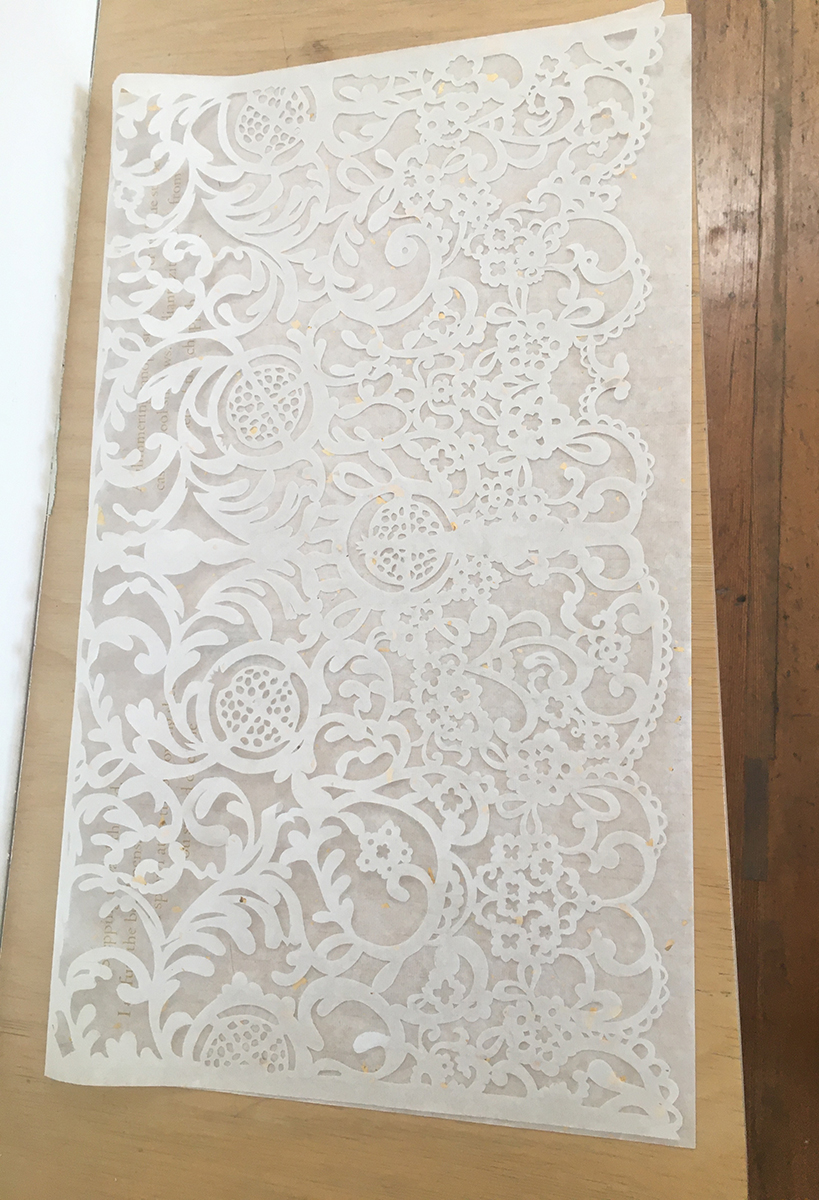

My body of work uses a wide array of mediums, most commonly sculpture, photography, letterpress printing, and bookbinding, to explore my own devotional experiences/romantic love towards G-d/piety and devotion in both contexts. I integrate recontextualized ritual and apotropaic objects, my own body, leather, text, silicon, rope, paper, and silk, to express a vulnerable, genuine expression of my own experiences, emotions, beliefs, and religious practices rather than anything political or critical.

I am especially interested in dissolving the dichotomies between the holy and the profane and between public and private. I see Judaism as an embodied religion. More than belief, it emphasizes behavior and, in particular, ritualized action: certain movements or gestures, things to wear or wrap oneself in, substances to be ingested, and scents to be smelled. In my artistic practice, I replicate these actions by physically engaging with sculpture that unites queer and Jewish ritual objects. In these interactions, I play with gender, sexual, and ethno-religious identity. When I make my sculptures and books, I teach myself ceremonial techniques and work slowly and with intention to activate the religious function of these objects.

In Deuteronomy 30:12 it is said “[G-d’s word] is not in the heavens.” Judaism is a centuries-long debate with each other and with G-d. Israel, translates to G-d-wrestler, who we are as a people is G-d wrestlers. The Torah is a living document, the Talmudic sages were just Jews with opinions, living a long time ago, engaging with Judaism and recording their opinions and we are also Jews with opinions, living today, engaging with Judaism, and if we write our stuff down we are just as valid. The verse continues with “[the Torah] is very close to you, in your mouth and in your heart, to observe it.” Torah is not a specific list of rules handed down by a central authority, it lives in our actions and in our souls, in the holy words we recite and in the inner compass that points us towards good actions. Torah is in our mouths and our hearts, in our orifices and openings stretching wide and wet, in the food on our tongue and in the songs we cry out, in our words of argument and our moans of desire, in our love for each other and in our love for Shekhinah above.

As a Jew and a queer person, history is vital to me, both in the sense of an ancient tradition held alive through a chain of memory and the act of excavating history. I love historical artifacts and cultural and sexual histories, and find freedom in giving myself permission to write and rewrite my own and my people’s story. I investigate memory, gender, human connection, vulnerability, how power is marked on the body through gestures and clothing, and the deeply romantic relationship between humanity and G-d. I learn through making, touching, and yes, taking into my body.