Sarah Frances

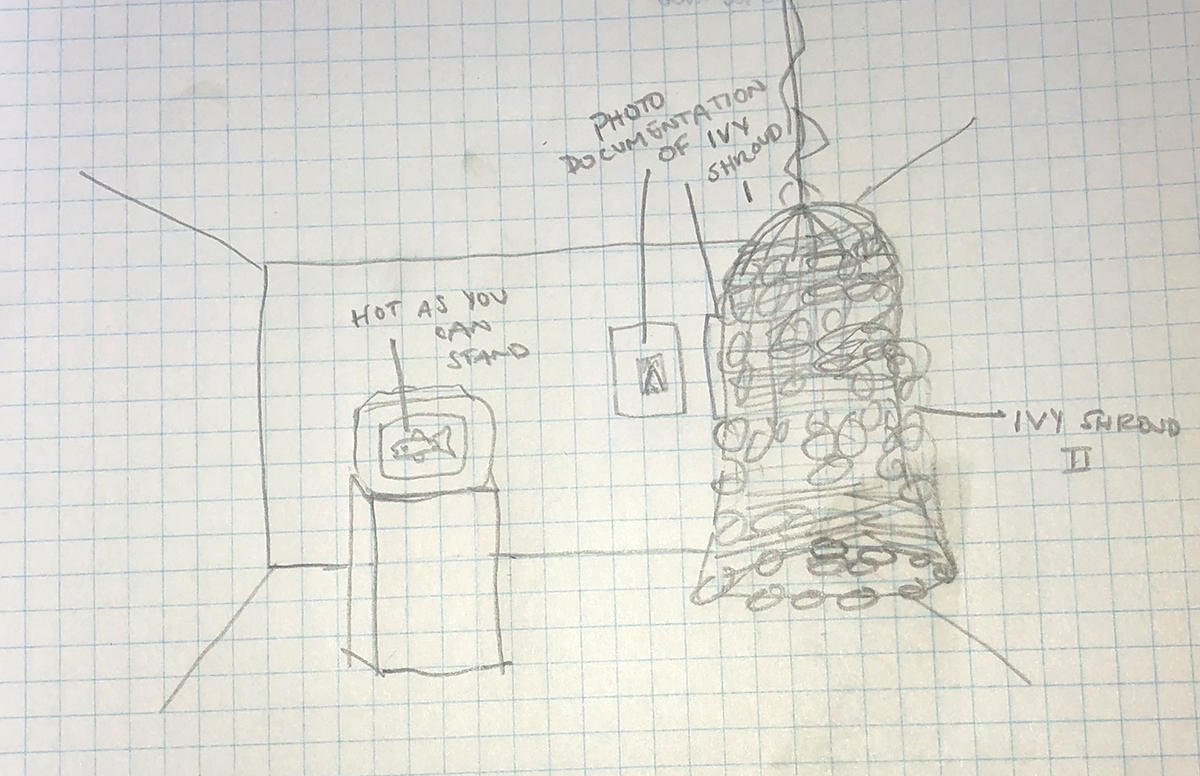

Running my hands over my bare skin, I can feel the impressions of time: the wear of each day and the weight of each uncertainty. In the spring of 2019 I spent hours peeling back invasive ivy from the flaking bark of trees and ran my hands over the newly exposed grooved trunk. I wove the ivy into a shroud so viewers could stand beneath it and feel the validation of a physical invasion.

Ecosystems that are subject to rapid change, by the loss of a key species or the introduction of foreign invasive ones, become destabilized. The ecosystem sometimes regains its balance, and sometimes does not. Humans bounce from foot to foot, hanging onto fleeting moments of stable ground.

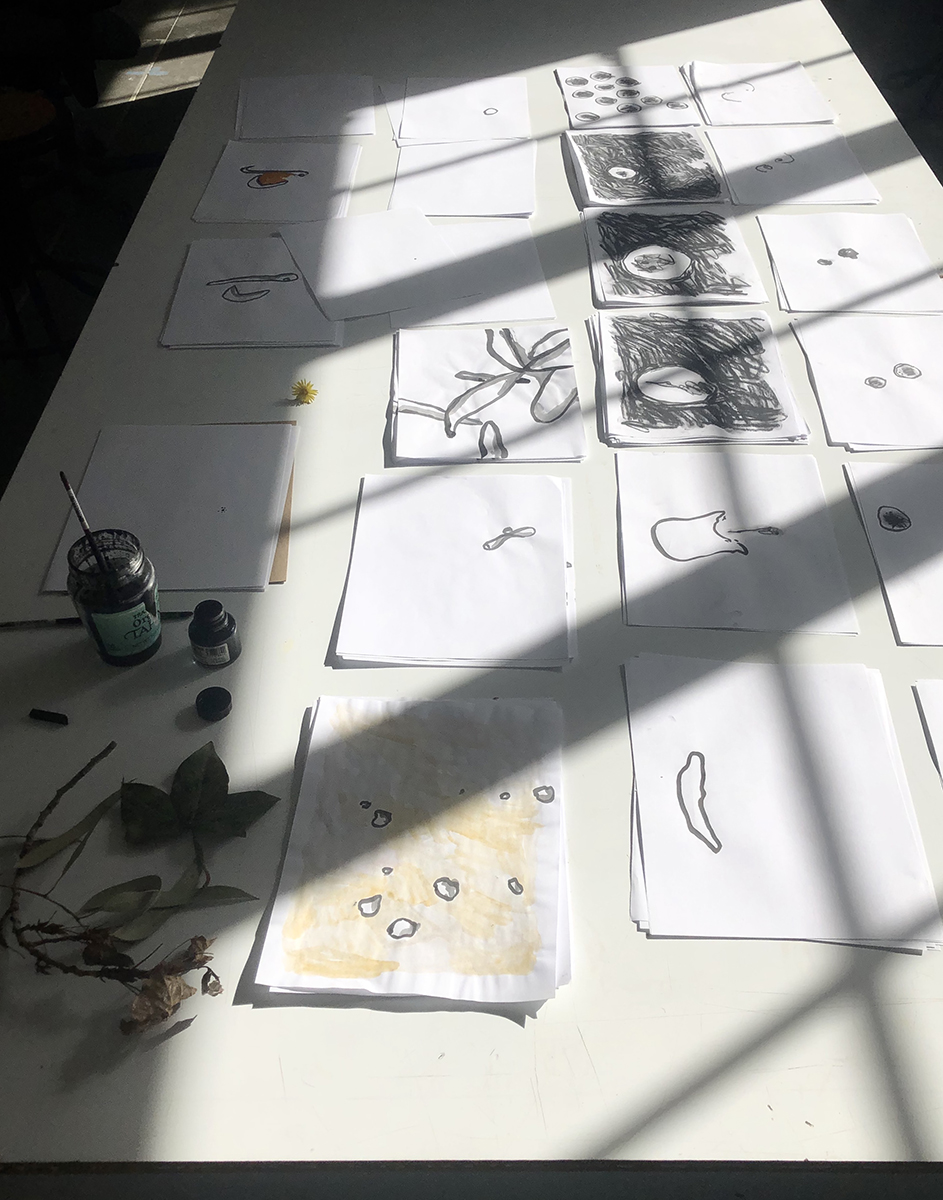

I am curious about how we can learn from the Earth’s mutability and how we can use this knowledge to heal. In a world that is defined by change, I still find myself with an overwhelming desire to collect, compile, archive, and hold on. I find myself materializing time, drawing it into form, dragging it behind me, wearing it as a second skin.

In the winter of 2018, I spat sediment from the Columbia River into a large ceramic sink and then fired it. This was a way for me to preserve the ever shifting land that raised me, to see exactly what would happen if I transformed impressionable Earth into a solid object that can be displayed on a white pedestal. I carried it with me as a personal item on my United Airlines flight from Portland to Oakland.

I am inspired by the work of the anadromous Pacific Salmon, whose bodies shift to accommodate their travels from freshwater to saltwater. Who return home to spawn and who die from the grueling labor of reproduction. Whose flesh feeds all that ask.

I want to know how it feels to give my body up to biology; to feel each new impression as nothing but evidence that change has taken place and that time has passed. I long for the freedom of total, uncompromising transformation. Of leaving and then coming back. I wonder about the burden of fertility in such precarious times.