V. Colonialism and Rupert García's Prophecy of Death

- Isabella Perry

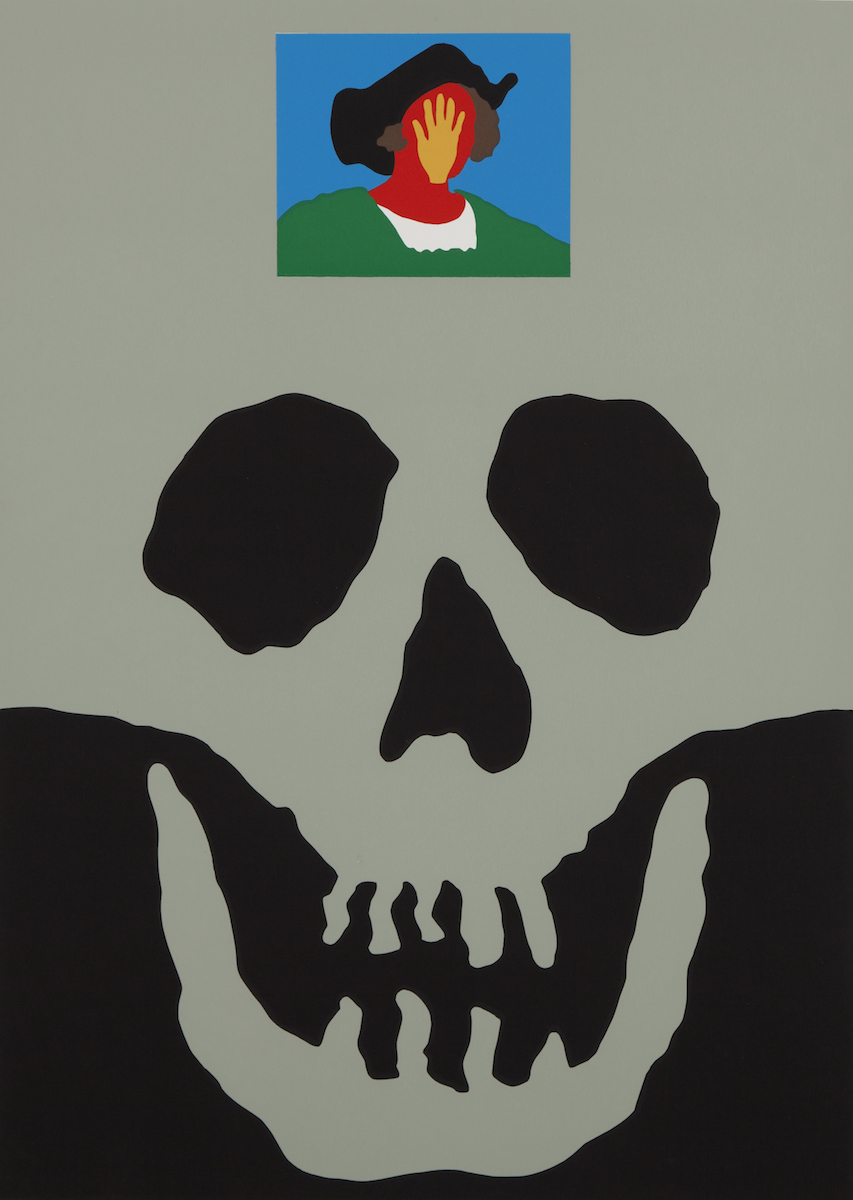

Rupert García’s Calavera Crystal Ball (1992) is a serigraph (screenprint) on paper depicting a skull and Christopher Columbus with a hand obscuring his face. (Figure 12) The majority of the composition of the piece consists of a simple black and grey skull. At the top center of the print is a small square in which Columbus is depicted wearing a green garment and a black hat, against a vivid blue background. Columbus’s skin is red and he lacks any facial characteristics. Instead, a yellow hand is placed where his face would otherwise be. The depiction of Columbus is limited to a small square, while the skull does not have any endpoint, its coloring continuing to the borders of the print. The content, composition, and style communicate a grim reality of the past and probable future.

Figure 12

Figure 12

As an artist who was active in the political movements of the 1960s and 1970s, and whose art is comprised of political and social defiance, García addresses the violence of colonialism in this piece. While throughout history there have been many oppressors both within settler colonialism and outside of it that have taken part in the destruction of cultures and the people within them, we have been taught Columbus was the first European man to come to North America. García relies on Western society’s mass teaching and celebration of Columbus as a “discoverer” in which most people in the United States can identify an image of him. In fact, the composition of García’s depiction is reminiscent of one of the most widespread paintings of Columbus, made by Sebastiano del Piombo in 1519. (Figure 13) Even the single characteristic of Columbus’s hat gives viewers enough information to identify who García is representing.

Figure 13

Figure 13

This fact points to Columbus’s dominance in the collective Western imagination. García is thus able to portray Columbus in a way that is completely recognizable to viewers while giving him no facial characteristics and minimal detail. Rather than depicting Columbus as a hero, as del Piombo does, García portrays him as a man with little value who caused mass destruction of native peoples and land, actions that perpetuate settler colonialism today. While the depiction of Columbus in this print is small, his presence cannot be ignored because he is placed at the very top of the composition and he is the only part of the image that is not black and grey. The hand covering his face might symbolize that who Columbus was as a person—his beliefs and actions—are of no value compared to the destruction that he caused, which is seen by his placement atop the massive, never-ending skull. Not only does the hand disguise his face, it is also an aggressive use of symbolism that people may interpret as a stop sign, a rejection, or a hand smothering him.

The flat planes of color are in stark contrast to the large black and grey skull. García carefully chose the colors in order to not make colonialism and the death of native people bright or romanticized. He chooses to use grey over white possibly because grey evokes melancholy feelings, while white symbolizes purity and innocence, as well as the European colonialists themselves. While the skull is easily identifiable, it is somewhat abstract and resembles an inkblot test. The teeth are crooked and jagged, and the black negative space between them looks as if there could be some figure within it. Skulls are common motifs in Mexican folk art, which García studied and used in his work.1 However, the skull in this piece is not being used to honor a loved one, but rather to represent the slaughter of native people and the violent legacy of colonialism. García takes advantage of the spatial limitations of a 30 x 22 inch sheet of paper by using the space he has to illustrate that the deaths of people from settler colonialism is never-ending, borderless, and too large to ever be able to depict. The skull that bleeds to the edges of the paper gives the viewer the ability to decide where they think the death might stop.

While García created this piece in 1992, 500 years after Columbus’s arrival in the Americas, it is just as relevant today as ever. Settler colonialism never stopped and settlers are still here, occupying this land.2 Colonialism is inherently tied to capitalism. People who are in power need colonialism to continue so they can continue to extract resources and accumulate wealth. Violence against people of color in general and specifically native and Black people—two groups who were targeted in early colonialism—all stems from settler colonialism. Many modern day violent acts, including racial and gender-based violence, can be traced back to the origins and structures of settler colonialism.

Throughout his career García has used his art to make political statements. He was active in movements that challenged racism and the military recruitment of Latinx and Black young people.3 He was specifically involved in Bay Area activism, where he contributed images like *N.E.W.S. to All (*1993) and ¡Cesen Deportación! (1973) that motivated the movement and sparked thinking. (Figures 14 and 15) The reproduction of his poster-based art allowed many people to see his work. Both reproduced and printed with limited editions, the art was both special and accessible. García was active across many decades, and much of his art is reminiscent of other artistic movements, including Mexican folk art and American pop art. Much of his work is comprised of simple color blocking, using color in a way that is both slightly outlandish and bright and also in the most minimal way possible. All of the bright colors in Calavera Crystal Skull are of a flat tone, rather than used for shading. Though this particular piece was made 27 years ago, it still appears vivid, bright and modern.

The artistic movements that García was involved in continue today, both in aesthetics and messaging. This piece is relevant within this exhibition as it addresses themes of land, assimilation, and colonialism from the perspective of colonized people of color. As this show is focused around the Bay Area, García’s work is representative of the history of the Bay Area and speaks to the current political moment. Over the past few decades, many of the issues García was fighting against have continued and in some ways have gotten worse. Under Trump’s presidency, people of color and especially the Latinx community, have been targeted by disillusioned white people.

In our current society the number of people in poverty rise, as the wealth of the very few increases. As industrial jobs decrease with outsourced labor and the development of new technologies, people become economically displaced. Middle and lower class white people who lose their jobs blame their situation on scapegoated minorities. Societal movements arise that focus on ridding the country of the targeted group to return to an imagined better time. They are choosing to blame their current job struggles on immigration, rather than on the political changes and the wealthy people that benefit from them. Middle class and wealthy white people have also participated in racism as a means to secure their own interests. This represents the development of settler colonialism, as it has continued since slavery and the genocide and theft of native land and native people.

Within the broader exhibition focused on land, violence, assimilation, and race, many viewers seeing Rupert García’s Calavera Crystal Ball may make a clear connection to colonialism, offering context and connections for other works in the show that may be more difficult to decode. The title of the piece, a composite of Spanish and English with “calavera” meaning skull in Spanish, evokes a prophecy of death. The seemingly contradictory combination of the skull, which represents death and ending, and the crystal ball, which represents what may be coming, either foreshadows a gruesome future or speaks back to the past. One interpretation of the piece’s title along with its symbolism could be that García is sending a message to Christopher Columbus, as if saying to him: look at what your actions have done. Alternatively, García may be sending a message of warning to us, about our own future. In both of these interpretations, his piece is the crystal ball itself, revealing the truth about the future that is yet to be seen.

- Mark Johnstone and Leslie Aboud Holzman. Epicenter: San Francisco Bay Area Art Now. (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2002). ↩

- Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society. vol. 1, no. 1 (2012). ↩

- “Rupert García,” Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2019, americanart.si.edu/artist/rupert-García-1732. ↩

| words