III. Black Hair Care as Art

- Fiona Ordway Mosser

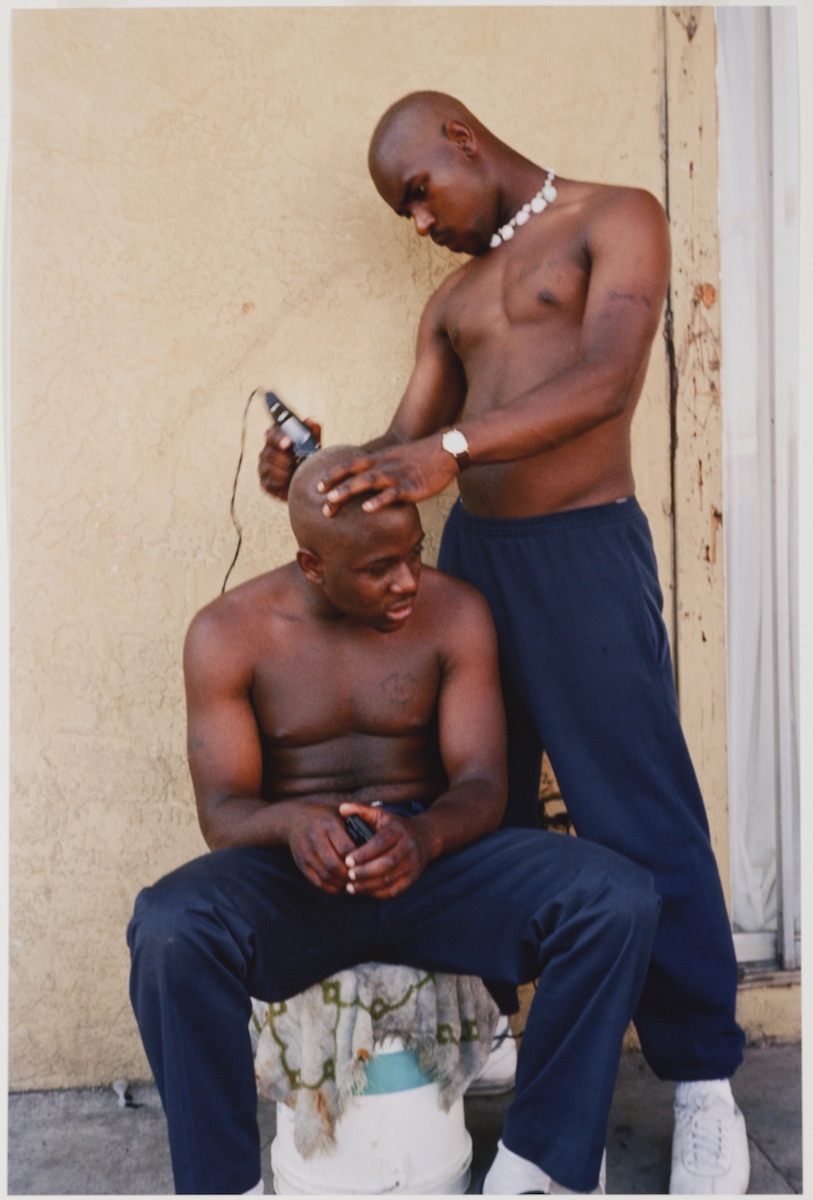

Black people have been seriously misrepresented in the United States: from daguerreotypes to mammies, to blackface and mugshots. In popular media Black men are often dehumanized and portrayed as hyper-masculine and violent. Black photographers have challenged this misrepresentation by depicting their own communities. Intimate Cut is a photograph of a Black man cutting another man’s hair in East Oakland in 2000.(Figure 5) The title speaks to the aura of the photo: intimacy. This photograph challenges stereotypes of Black men and offers a glimpse into the sacred space of Black hair care. The photographer, Traci Bartlow, is a visual and performance artist from Oakland. Bartlow was a hip hop journalist in the 1990s, and her photography was featured in the Oakland Museum of California’s 2018 exhibition RESPECT: Hip Hop Style & Wisdom.

Figure 5

Figure 5

Black trauma is often more visible than Black love or Black joy. In Embodying Black Experience: Stillness Critical Memory, and the Black Body, Harvey Young writes, “The Black body, whether on the auction block, the American plantation, hanged from a light pole as part of a lynching ritual, attacked by police dogs within the civil rights era, or staged as a ‘criminal body,’ by contemporary law enforcement and judicial systems, is a body that has been forced into the public spotlight and given a compulsory visibility.”1 Black people are frequently depicted in the context of violence and trauma, and these are the images of Black people that are most often shared in media. Bartlow resists this by depicting Black men in a different context. The men are shown in community and caring for each other.

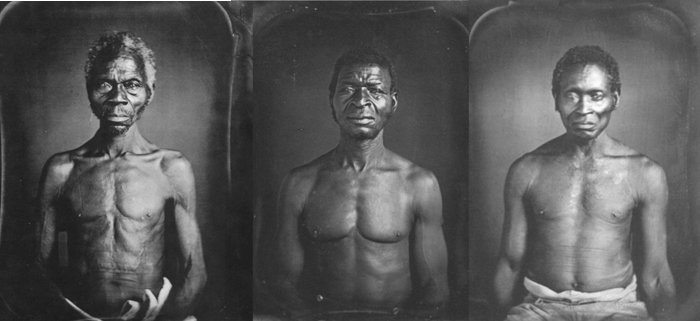

There is a long history of white people controlling the image of Black men. This has its roots in the enslavement of Africans. White people justified their enslavement and violence against Black men by seeing them as less than human. Daguerreotypes, an early form of photography popular in the 1840s and 1850s, depicted a dehumanized vision of African Americans.(Figure 6) The daguerreotypes depicted Black captives that were forced to strip down and pose in front of the white man behind the camera. These images were used to prove Black people’s difference from white people and their inferiority. The daguerreotypes affirmed the white power over Black people and their image. Since early daguerreotypes and photographs of Black lynched bodies, Black people have reclaimed photography in order to adequately represent themselves. Late 19th century and early 20th century photographers like James Van Der Zee, Cornelius M. Battey, Arthur P. Bedou, John Johnson, Addison N. Scurlock, and Gordon Parks portrayed African Americans with respect. Young writes, “There is a power in the photograph; it affords the agency to refute ‘representation of us created by white folks’ through its ability to document ‘reality.’ This image of lived reality carries within it the potential to challenge and, possibly, erase stereotypes and caricatures of Blackness.”2 In Intimate Cut, Bartlow challenges the hyper-masculine and violent stereotypes of Black men. Intimate Cut speaks to the femininity that resides in men. One man is wearing a necklace, they are caring for their beauty.

Figure 6

Figure 6

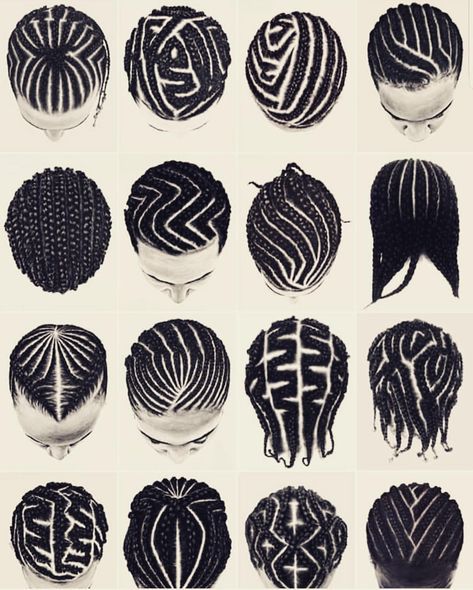

Black hair care is both spiritual and political. In African culture, hair holds cultural significance and is thought to contain spirit. Hair is adorned with shells, beads and fabrics, and hair is braided and shaped into different complex designs. (Figure 7) During the transatlantic slave trade, rice was braided into hair by slaves coming to the Americas and hair was braided into maps that lead slaves to freedom. In the Americas, captive Black people were prohibited from showing signs of their culture, so slave owners would force slaves to cut and cover their hair. Today in America, Black hair is still policed. Black people may feel pressured to cut their hair or have a more Eurocentric style in order to secure a job, or they may be forced to change their hair for school, sports, and the military. Although natural hair was popularized in the Black power movement beginning in the 1960’s, white supremacy has a firm grip on society and natural hair still can lead to more discrimination.

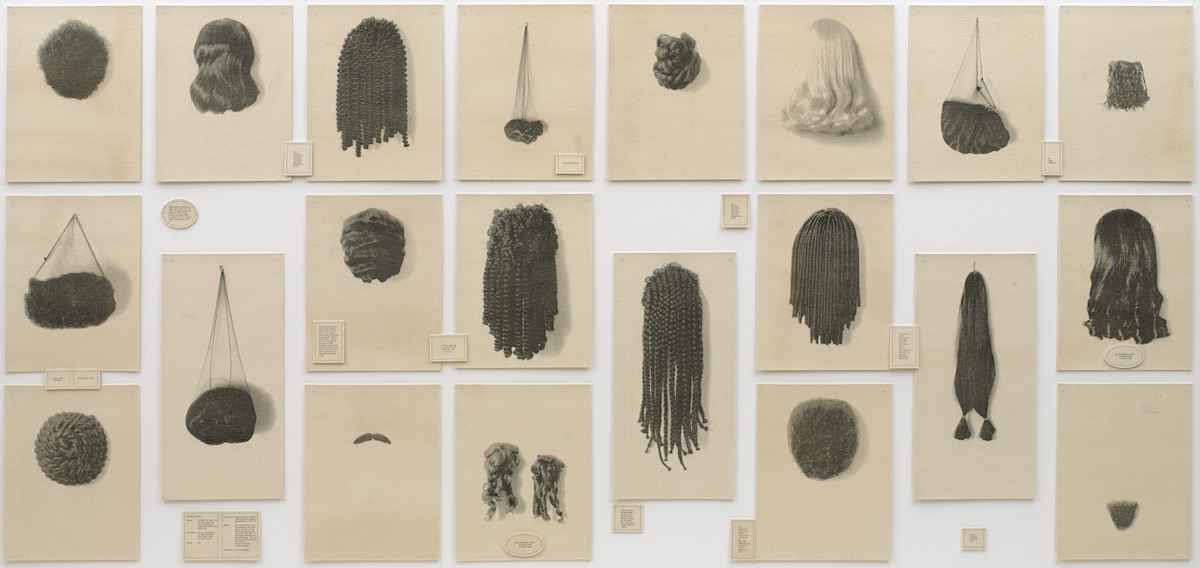

Caring for Black hair is an act of cultural preservation and is an art in itself. Another photographer, Carrie Mae Weems, has also depicted hair care in her art. One piece out of her kitchen table series shows a woman and her mother, who is brushing her hair at a kitchen table. (Figure 8) Other artists, like David Hammons have used hair as a medium in fine art. In his piece Nap Tapestry, dreadlocks are hung between hair woven on wire into traditional African patterns. (Figure 9) Hammons reframes natural Black hair as a traditional African art form. Lorna Simpson also incorporates hair into her art. In her piece Wigs (Portfolio), different wigs and hair pieces are displayed. Each wig and hairpiece has different connotations. (Figure 10) The hair becomes a way to analyze race, gender, and class, and our assumptions of what certain styles of hair represent.

Figure 8

Figure 8

Doing hair creates community. In an ethnography of barbershops, Bryant Keith Alexander writes, “I find that it is one of those few moments when men—and for me, Black men—come into an unacknowledged yet sanctioned intimate contact with each other. We understand the meaningfulness of the engagement, not only in the functionality of the action but in the knowing. The knowing—that a Black man who knows and understands the growth pattern of Black hair and the sensitivity of Black skin—is caring for another Black man.”3 Intimate Cut speaks to this intimate space created while men getting their hair cared for. In her photography, Bartlow preserves a moment of community care. Hair care happens inside barbershops and in personal residencies. Friends and family will often do each other’s hair from home. Sometimes barbers and hair stylists will work from home too. While people are having their hair cared for they share knowledge and stories. In Cutting along the Color Line: Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America, Quincy Mills writes, “It was not uncommon for owners, especially those who were self-described activists, to use their shops to conduct meetings or distribute literature on protest campaigns.”4 Spaces of hair care become hubs for community.

Oakland has historically been a home to diverse communities and a hub for activism. Unfortunately, as gentrification spreads across the Bay Area, these aspects of Oakland are threatened. Quincy talks about how development has threatened barbershops, “Urban renewal—or, as many black residents labeled it, ‘Negro removal’—directly affected barber shops. To be sure, urban renewal did not create a moment of crisis for black barber shops, but it did cause concern for owners who were asked to close their doors and patrons who were forced to consider a new shop and a changing neighborhood.”5 As the Bay Area is rapidly developed and more and more white people move into the area, displacing Black folks and other people of color, barbershops and other hubs for the Black community are threatened by high rents and waves of displacement. East Oakland was once where marginalized people were able to afford homes and find community, but now people are being pushed out. Bartlow’s documentation of Black communities records their culture and history. Young writes, “The photograph pauses the flow of time and grants the viewer a privileged glimpse into a moment that no longer exists. It enables an encounter with the past even as it compels us to acknowledge that our present and indeed, our future will soon have passed.”6 Bartlow’s photographic work documented a culture that is now in danger of being lost to gentrification. As tech workers flood to the Bay Area and development increases, the future of Oakland is unclear.

Intimate Cut brings a snapshot of the real East Oakland to the Mills campus. The Mills College Art Museum sits in East Oakland, a primarily Black, Latino, immigrant, and working class neighborhood, yet the vast majority of the art in the collection does not speak to this community. There is a stark difference in cultures on campus and off. While East Oakland is a very community orientated and diverse place, with mostly working class occupants, Mills lacks the sense of community that is present off campus. Although East Oakland is seen by some as “the hood” or unsafe, it is primarily a community of families deeply rooted in Oakland. Oakland carries a reputation of being dangerous because of white people’s fear and misconceptions about Black and brown people. Mills feeds into this fear by having a barbed wire fence and a policed gate that separates the Mills community from the greater community of Oakland. These fences prevent Mills students from interacting with East Oakland residents. Intimate Cut counters the fear and stereotypes of Black people. Traci Bartlow’s photograph is usually hidden away in the Mills College Art Museum’s storage. This show liberates Intimate Cut from the museum’s collection, bringing this much needed depiction of Black masculinity into view.

- Harvey Young, Embodying Black Experience: Stillness, Critical Memory, and the Black Body. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), 12. ↩

- Ibid., 57. ↩

- Bryant Keith Alexander, “Fading, Twisting, and Weaving: An Interpretive Ethnography of the Black Barbershop as Cultural Space,” Qualitative Inquiry 9, no. 1, (2003), 120. ↩

- Quincy T. Mills, Cutting along the Color Line: Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 140. ↩

- Ibid. 246. ↩

- Young, Embodying Black Experience, 57. ↩

| words