Dario Robleto: The Heart is a Metaphor, But Also Not

- Anne Lesley Selcer

Dario Robleto’s obsessions extend inward to the most unseen places and outward to the outermost spaces of the human unknown. He wants to study, understand, and memorialize the cultural objects of these spaces as well as propose new ones. His deeply humanist practice hinges on a drive to research, magnify, and make homage to the human archive.

Figure 15

Figure 15

Cyanotypes, prints, watercolor paper, butterflies, butterfly antennae made from stretched audiotape of the earliest live recording of music (The Crystal Palace Recordings of Händel’s “Israel in Egypt,” 1888), various cave minerals and crystals, homemade crystals, black swan vertebrae, lapis lazuli, coral, sea urchin shells, sea urchin teeth, various seashells, ocean water, pigments, cut paper, mica flakes, glitter, feathers, colored mirrors, plastic and glass domes, audio recording, digital player, headphones, wood, polyurethane. Robleto’s art work Setlists for a Setting Sun (The Crystal Palace) is an homage to the first recorded music, which was made possible by the enormity of the London World’s Fair. On June 29, a Friday, the sound waves of an orchestra of around 500 musicians and the voices of 4,000 people were pressed into the large wax cylinders of a freshly invented phonograph. The recording sounds ethereal and distant today, a thrilling echo. Georg Friedrich Händel’s composition was performed for 23,722 people, a spectacle made possible by the 956,165-square-foot exhibition hall. The Crystal Palace was the first mass-produced building, and as such, was the perfect site for the brand new forms of infinity announced by this feat.1

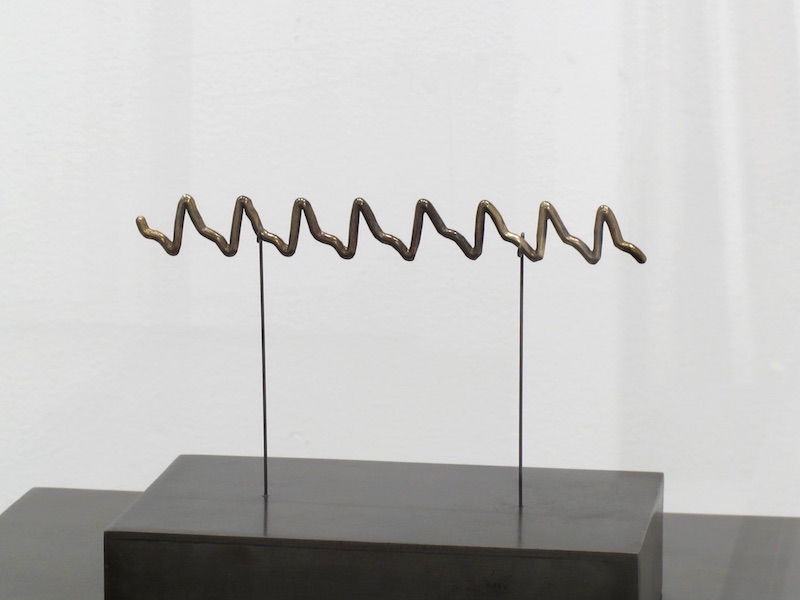

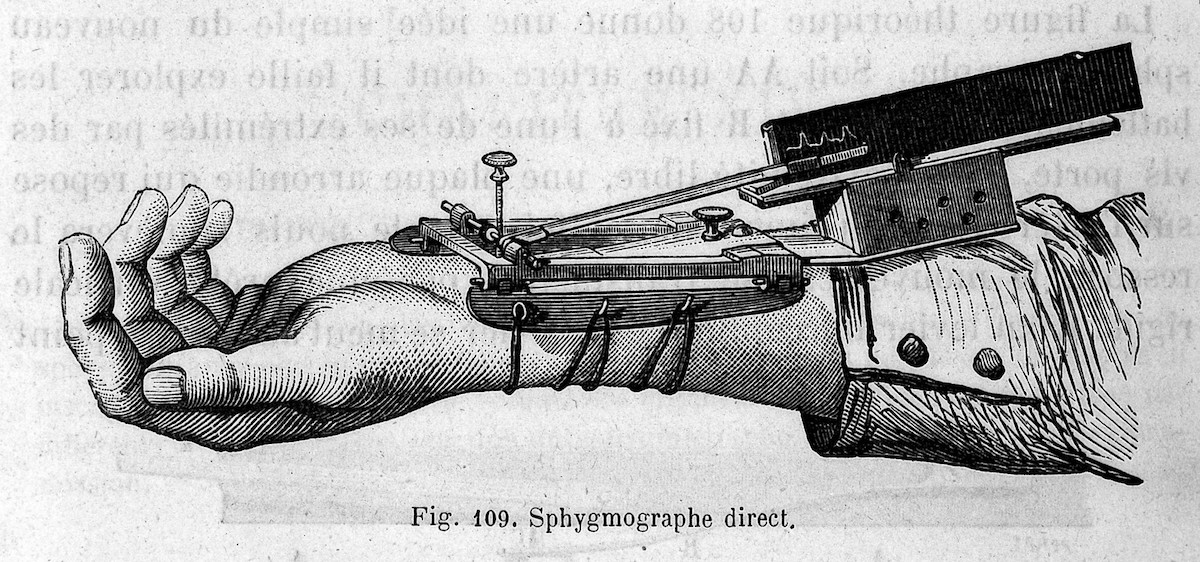

Robleto is interested in human rhythms. Thus, the artist narrativizes representations as human flows archived in cultural form. Just as rhythms can give rise to new forms of representation, representations can give rise to new rhythms. As rhythms and representations repeat, pattern, pick up, and feed indistinguishably into another, admixtures of human culture emerge. When Karl von Vierordt recorded the first heartbeat in the form of a “pulse picture” in 1853,2 no material was sensitive enough to record this image without disturbance but a piece of soot attached to human hair. These were the materials of the very first waveform we now recognize as the pulse of the human heart. Von Vierordt recorded 50 heartbeats, birth to death. The monumental pair of sculptures Love, Before There Was Love represent the “earliest waveform recordings of blood flowing from the heart both before and during an emotional state (1870).”3 The artist has memorialized this emotional event in large-scale brass-plated stainless steel. There are “outtakes” from this project—the first time the heart was recorded while someone was eating chocolate, the first time the heart was recorded while someone was smelling lavender.

Figure 16

Figure 16

“The cardiograph was like the microscope or telescope, but it’s not talked about that way—there are a handful of devices that are like that. There is a before and an after,” says Robleto. “Mid-19th century science is really trying to pull the heart away from mystical understanding. They needed to prove it was not the domain of the social. Yet romanticism and religion were the scientist’s personal history.”4 In a sort of synthesis, Robleto’s art both honors and answers science. His work embodies an insistence on seeing the objects of the Western archive complete with their human stories, cloaked in their auras, with their beauty.

Cut and polished nautilus shells, various cut and polished seashells, various urchin spines and teeth, mushroom coral, green and white tusks, squilla claws, butterfly wings, colored pigments and beads, colored crushed glass and glitter, dyed mica flakes, pearlescent paint, cut paper, acrylic domes, brass rods, colored mirrored Plexiglas, glue, and maple. The glass vitrine containing Small Crafts on Sisyphean Seas, full of carefully arranged treasures, is a proposal for an “initial gift” to whatever life may dwell in outer space. Says the artist, “Scientists always send math. They think in light waves instead of sending objects. I like the idea that first contact is an exchange of gifts.” He asks, instead of sending the Fibonacci Sequence, why not send the seashell? This gift is arranged as a diorama of strange and luminescent fetishes. They evoke both the design of the past century and a fantasy of the unknown future. The Golden Spiral, the form which results from the Fibonacci Sequence, is “self similar,” meaning its shape is infinitely repeated when magnified. Culture works something like that too. Robleto is interested in the rhythms and representations of being alive in human form. Here we have artist-as-lover to human life, the one who attends to, studies, memorializes, embellishes upon, and communicates its events to others, embracing its dearly important moments, creating new representations that carry it on.

Notes

- Olalquiaga, Celeste, The Artificial Kingdom: A Treasury of the Kitsch Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988). ↩

- Dario Robleto: The Boundary of Life is Quietly Crossed (Houston: The Menil Collection, 2015). https://bit.ly/2lRXWi6 ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Writer’s conversation with artist, May 14, 2019. ↩