Kathryn Andrews: Censor or Surfeit

- Joanna Fiduccia

In 1823, the satirist Ludwig Börne penned an essay titled “The Art of Becoming an Original Writer in Three Days,” in which he advised his readers to record everything that passed through their minds, every opinion and idle thought. This three-day brain-dump was intended to drum out what Börne called the “disgraceful cowardliness in regard to thinking that holds us all back—an anxiety about social approbation, more repressive than the censorship of governments.”1 It was an idea that would be made famous by one of Börne’s readers: Sigmund Freud. Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams (1900) pivots on internalized censorship, and yet it was only two decades after its publication that Freud realized, to his surprise, Börne’s early influence on his thought. A striking example of cryptamnesia (forgetting an idea so that it strikes us as our own when the idea returns to mind), Freud’s psychic censorship occurred ironically, as Peter Galison notes, “just at the moment that Freud is addressing the originality of his idea of … psychic censorship.”2

Figure 1

Figure 1

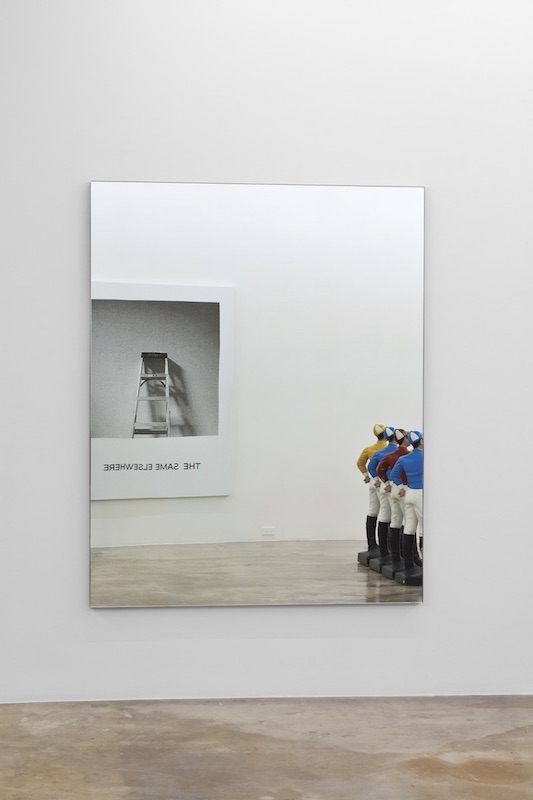

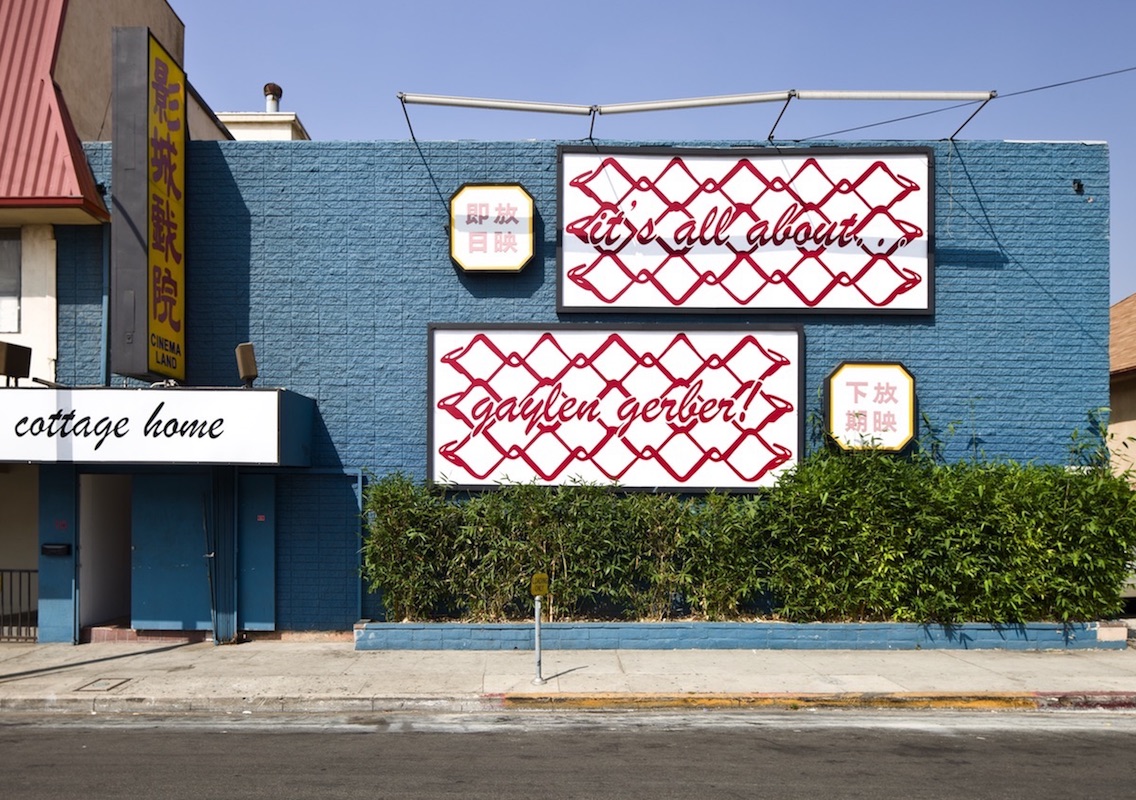

This morsel of intellectual history puts us on the scent of Kathryn Andrews’s work. Andrews traffics in a range of objects and images so generic as to belong to no one, like balloons and baseball caps, stock photography (or photographs Andrews styles to resemble it), and the gleaming chrome or stainless steel elements that appear so regularly in her work as to suggest a signature—except that their primary virtue is to look entirely untouched by anything personal or particular. Other works pressure the terms of Andrews’s authorship: for instance, her puckish participation in the 2010 group exhibition “Support Group,” to which Andrews contributed two billboards braying “it’s all about … gaylen gerber!”; or Baldessari (2010), a mirror installed in the Rubell Collection to reflect, like Perseus’s shield, John Baldessari’s 1977 Goya Series: The Same Elsewhere.3 In these examples, Andrews’s work (her labor as well as her oeuvre) inheres in a relationship that appears by turns complementary, parasitic, and antagonistic. Appropriation, with its neat assignment of authorship and its will-to-mastery, is surely not the right word for it. Instead, like Freud and Börne, Andrews incorporates these objects and artworks only to set spinning the involutions of originality.

Figure 2

Figure 2

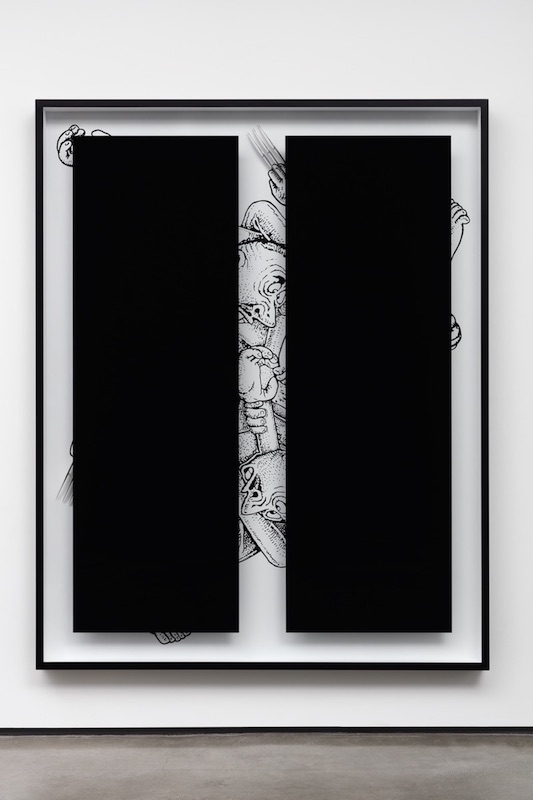

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the works featured in In Plain Sight. Each work in Black Bars, a series Andrews began in 2016, consists of an image printed at an imposing scale and mostly obscured by two vertical black bars. What appear from afar like redactions are, on closer inspection, black rectangles silkscreened onto the acrylic picture glass, which is set in deep frames. By approaching the works, one can throw an oblique gaze under the bars to glimpse more of the images: the scrabble of limbs from a Basil Wolverton drawing, an icon of a broken heart, a sketch from a cartoon sequence in which Bugs Bunny flees a blank box. Violence or its threat provides the through-line. Sandwiched between the silkscreened glass and images of Black Bars are a set of objects, including a replica of Wolverine’s claw that puns on Wolverton’s name, and the gun featured in the movie Mr. and Mrs. Smith, its barrel pointed down the jagged rift in the heart. These props—a frequent ingredient in Andrews’s work—are a near perfect inversion of the auratic artwork of old whose aura is derived from, rather than destroyed by, their existence as cinematic images. In their transition from props to collectors’ items, these objects bear with them the trace of celebrity, a value that the otherwise worthless prop acquires post hoc.

Figure 3

Figure 3

The prop, however, is something of a MacGuffin. Props provoke us to think about the absent body of the celebrity, but the conspicuously absent body is, in fact, Andrews’s. Like Lutz Bacher and Cady Noland, Andrews approaches a critique of power—in the violence of the images she references, no less than in the two art-historical movements amply referenced in her work, Minimalism and Pop Art—through the magnification of dominating structures that appear natural, a matter of course, or merely aesthetic. Andrews reasons that feminist positions in art practice that have historically worked to recenter aesthetic experience on women’s embodied existence are too quickly categorized and assimilated. Instead, for a body, she leaves us with one of two things: a line of lounge chairs occupied by a sheaf of rolled-up sun umbrellas, whose stainless steel posts transform the beach accessory into a stockpile of javelins; or the reflection of our bodies as they are caught in the dark glass of the black bars—body as weapon, or body as flattened image.

Like the prop, Andrews inverts the work previously done through the embodied artist—an emphasis on materiality that once complicated our apprehension of the artwork, but now seems mostly to cauterize it. Instead, she doubles down on the sleek and easily incorporated body of cultural objects in order to exacerbate their repressive quality. This is Andrews’s tightrope act, a feat of troubling our consumption of images in art by using the most assimilable aesthetics. We might call this strategy “refluxive”: a matter of encouraging such rapid consumption of the work that we are left with indigestion. In her work, the body that registers power is, in fact, our own, startled to find itself reflected in the sheen of images.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Notes

- Börne, Ludwig, “The Art of Becoming an Original Author in Three Days,” trans. Leland de la Durantaye, Harvard Review (2006): 75, qtd. in Peter Galison, “Black-out Spaces: Freud, Censorship and the Re-territorialization of the Mind,” The British Journal for the History of Science, vol. 45, no. 2 (June 2012): 237. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Curated by Michael Ned Holte at Cottage Home, Los Angeles, with Gaylen Gerber and Mateo Tannatt / Pauline. ↩