I. A Scene Untouched

- O. O. Roberts

Almost everyone has some connection with a formative domestic space in one way or another. This might be a childhood home, a past or present apartment, or merely a time in someone’s life. Domestic spaces are brought to life when occupied by the people who created them. When these spaces are empty, they still hold a memory of the occupant.

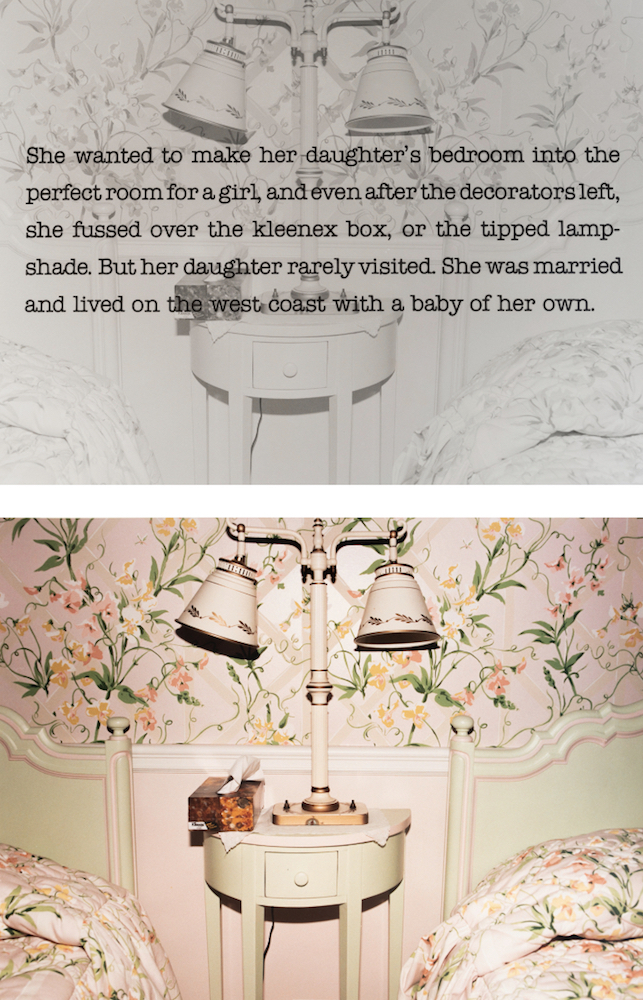

Ann Chamberlain (1956-2008) was an American artist living and working in the Bay Area who sought to examine the way spaces can hold memory and form identities based on their occupants. Her 1984 series entitled Domestic Interior consists of ten diptychs, each featuring a color photograph of an unoccupied yet lived-in space and a black and white version of that same photograph with overlaid text. Out of the ten pieces in the series, only one of Chamberlain’s works in the Domestic Interior series is being shown in the exhibition Unseen: The Hidden Labor of Women. This particular piece captures the isolation and forgotten labor of women’s work within a domestic setting and the context of motherhood (fig 1).

Chamberlain’s diptych examines the role of motherhood within a middle-class American household once the children of the house have grown up and moved away. This is the only piece in the series in which the space being captured does not have clear signs of being occupied. Everything in the photograph is clean, straightened, and perfectly manicured, awaiting an occupant. The accompanying text reads:

She wanted to make her daughter’s bedroom into the perfect room for a girl, and even after the decorators left, she fussed over the kleenex box or the tipped lampshade. But her daughter rarely visited. She was married and lived on the west coast with a baby of her own.

The photographs capture an untouched bedroom decorated with great care for a young girl. The sheets and the wallpaper match perfectly and are both decorated with delicate yellow flowers on a pastel pink background. Two twin beds create symmetry within the composition of the piece. The bed frames are painted a cool mint green that matches a small shared nightstand.

The text overlay shifts the tone of the piece. Upon reading the text, it becomes apparent that the mother of the household and curator of the space has put a great deal of labor, time, and care into creating a room that is perfect for her now fully-grown daughter. At first glance, the piece is welcoming and pleasant to look at, but as the viewer reads the text, the focus turns to the labor and isolation of the unnamed mother. Work performed outside of the traditional workforce, such as the time and care spent laboring in these domestic spaces, is often forgotten. This is especially true of emotional labor, like what is being performed in Domestic Interior.

The text points out how the mother of the house paid extreme attention to detail when decorating the space. Chamberlain points to the time and attention given to an orange and brown box of tissue sitting on the mint green side table and the tilt of the lampshade. She is not pointing these out because there is anything particularly important about these objects, but rather to show the amount of care and time the mother spent perfecting every small detail.

It is also important to note that the work required to create and maintain well-manicured spaces such as the one depicted in Domestic Interior is repetitive. The room has to be maintained even when it is untouched. Domestic spaces, both lived-in and unoccupied, require cleaning and upkeep. This means the mother of the house would need to enter these spaces countless times in order to maintain the neat finish of the room, even when the spaces remain unoccupied.

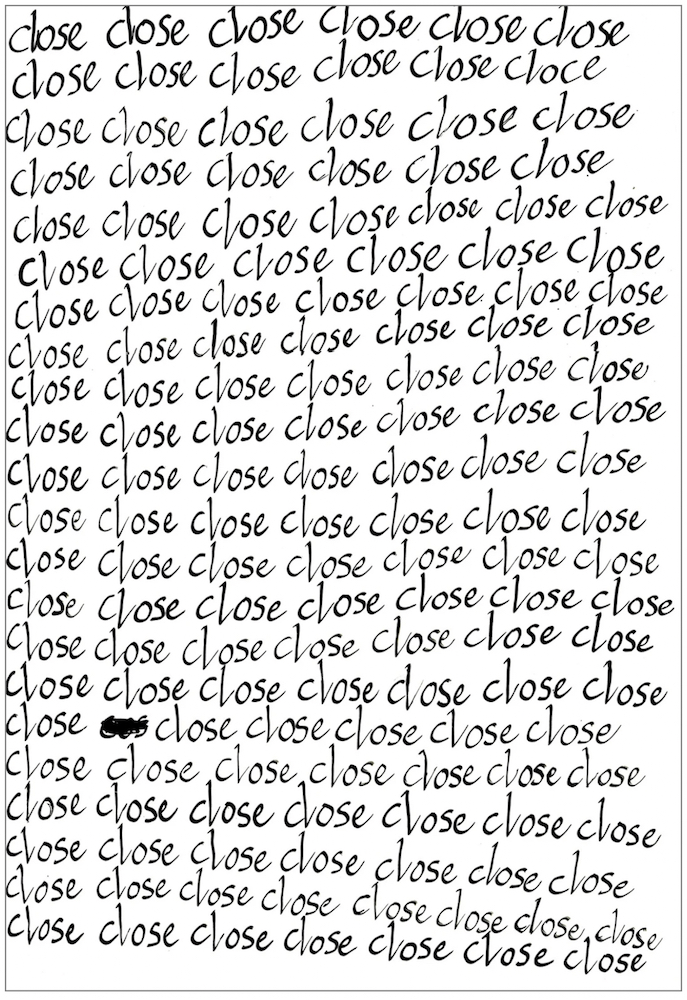

This is not the only representation of the repetition of women’s work in Unseen. Four pieces by Serena Scott that were acquired for the Mills College collection also examine the repetitive nature of women’s work. Each of Scott’s works are 19 x 13 inch ink drawings that feature a different word written repeatedly in tidy handwriting until the page is full. Scott’s repetitive lettering mirrors the repetitive labor required for maintaining a well-manicured domestic space like the one seen in Chamberlain’s work. Untitled (close) is the only piece of Scott’s shown in Unseen that has an error in the lettering that is crossed out (fig 2). This detail, whether intentional or not, reflects the fragility of repetitive work. Scott’s incorporation of her mistake allows the viewer to understand her process. In Domestic Interior, Chamberlain also gives the viewer a sense of the fragility of repetition by pointing out how the mother “fusses” with every detail in attempts to perfect her daughter’s room. While Scott and Chamberlain represent this in different ways, both their works think about time and process as a form of hidden labor.

The room, perfectly decorated, is clearly untouched and unoccupied. With this, Chamberlain is hinting at a different kind of repetitive labor, a generational labor, and more specifically, a feminized generational labor. The mother arranges the room for her daughter who has now taken on the role of motherhood herself. In turn, someday the daughter will most likely face the same position as her baby grows into adulthood. The viewer is confronted with how formative the role of motherhood is in constructing a feminine identity, especially for middle-class American women in the twentieth century.

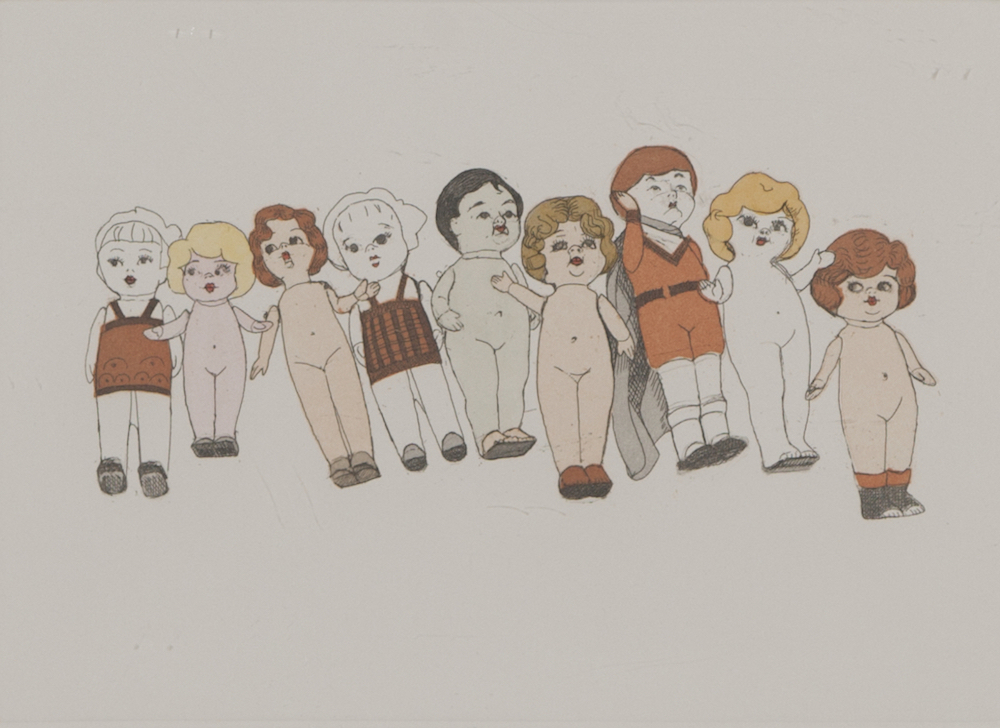

The role of motherhood is integral to the way young girls begin to form their own feminine identity. This is true even years before they are old enough to have children. Another piece in the exhibition, Beth Van Hoesen’s Nine Little Dolls, explores this idea (fig 3). The piece shows a collection of dolls that most likely belonged to a young girl. Historically one of the main reasons girls are given dolls, specifically baby dolls, is to teach them how to nurture and take care of something. This lesson is then again emphasized as they get older and begin preparing to enter adulthood, which for many of them will likely include motherhood. Once those girls are grown and have children of their own the cycle is continued.

Both Chamberlain’s Domestic Interior and Van Hoesen’s Nine Little Dolls examine the generational labor of motherhood. Van Hoesen examines the preparation for motherhood while Chamberlain showcases the loneliness of motherhood once children have grown up. In addition to these less traditional examples of the labor of motherhood, Unseen also features four more “mother and child” works including a print by Mary Cassatt (fig 4).

Ann Chamberlain’s Domestic Interior examines the isolation that comes with the hidden aspects of women’s work in a domestic setting and within the contexts of motherhood. Chamberlain’s decision to portray a mother and daughter relationship without depicting any people highlights the loneliness that can come with motherhood and domestic life. This is especially true once children have grown up and the cycle of motherhood continues for the next generation. This, in addition to the artist’s use of pronouns rather than names, allows the viewer to insert themselves into the scene, forcing them to question their position within domestic life.